Does the placement of the accused at court undermine the presumption of innocence?

15th December 2016

You may be lucky enough to have a lawyer represent you in court, but in many countries, you may struggle to hear what they say or to communicate with them. Over the last 20 years, docks, where the accused is located during trial, have become more ‘secure’, with some enclosed in glass or even behind wire mesh or bars. In 2014, Meredith Rossner from the London School of Economics and her research collaborators in Australia staged an experiment using a simulated trial in a real courtroom to test the effect of different docks on the presumption of innocence.

Courtroom architecture in the 21st century

Governments around the world are rethinking the function and design of courts. This is partly in response to budget cuts and austerity measures, and partly because of changing beliefs about what a court should look like. For instance, Her Majesty’s Court and Tribunal Service has recently announced a massive overhaul of the court estate across England and Wales, with the closure of 86 courts and tribunals as well as significant investment in new technologies. This has led to innovative re-thinking about court design, with proposed ‘justice hubs’ or ‘pop-up’ courts located within other buildings. A similar undertaking is currently underway in Ireland. In France, the centrally-located (on high-value land) Palais de Justice is to be moved further outside the city to a new high-rise court complex that boldly re-imagines what a court should look like. In these new plans, the aim is to develop justice spaces that can promote access to justice, democratic participation, and a more efficient system, while at the same time providing security for all users.

Figure 1. Proposed plan for new Paris Court Building, Renzo Piano Architects

We often think that courts embody immemorial tradition, with their weighty symbols and rituals of state power and authority. However, a close look at the history of legal architecture reveals fluid and dynamic conceptions of court houses and court rooms. But, as Linda Mulcahy argues in her book on legal architecture, while modern trends in justice have been towards increased transparency, due process and democracy, courts have actually become more confining and less democratic spaces. This can be seen most clearly in the criminal courtroom with the use of the dock for the placement of the accused at trial. Originally a holding pen for defendants held in cells below the court, docks soon developed into a segregated space for the accused to sit in the courtroom, traditionally a wooden box not dissimilar to a witness box or a jury box. In the past twenty years or so, docks have further evolved to include a more ‘secure’ variety which enclose the accused in glass so that they are completely separated from the rest of the courtroom. Such docks can now be found in courtrooms throughout much of the world, in countries with both common law and civil law traditions. Notable exceptions to this rule include the Scandinavian countries and the United States, which both sit the accused beside their lawyer at the bar table, as anyone familiar with crime dramas from these countries would recall. On the other end of the spectrum, Russia and several Eastern European countries routinely place defendants in docks surrounded by metal bars or mesh cages. We are familiar with this from the images of Pussy Riot in the dock during their trial in Moscow in 2012 (you can also find images of them in a glass dock here and here).

Isolating the accused in this way undermines their right to a fair trial and their right to dignified treatment. Given the current re-imagining of court buildings and courtrooms, it now seems a fitting time to revisit the peculiar persistence of docks in criminal proceedings.

What’s wrong with the dock?

There are three main arguments against the use of docks. The first has to do with the ability to hear proceedings and enjoy regular access to counsel. When segregated from the rest of the court, it can be hard to follow what is going on, to be seen and heard, and to consult with one’s lawyer. Early challenges to the dock centred on this, including cases from the seventeenth century, found in the Old Bailey Archives, where defendants would regularly request that they come out of the dock so that they can hear the case against them. This is the argument that eventually led to the decline of docks in America, beginning with cases such as Commonwealth v Boyd (1914) where a Pennsylvania court decided that, as a general principle, a defendant has a right to sit with counsel at the bar table. These developments foreshadowed arguments put forward to the European Court of Human Rights in the 1990s, where it was argued that confinement in a secure dock interfered with the accused’s ability to hear at trial.

The second issue with docks is that they might undermine the presumption of innocence, a right that is a cornerstone of modern legal practice. This argument has been made in several American cases over the course of the twentieth century, with one US Appeal Court Judge, who agreed that docks are “an anachronism in a modern criminal trial which could have been abandoned years ago,” concluded that:

‘The practice of isolating the accused in a four-foot-high box very well may affect a juror’s objectivity. Confinement in a prisoner dock focuses attention on the accused and may create the impression that he is somehow different or dangerous. By treating the accused in this distinctive manner, a juror may be influenced throughout the trial.’

In the UK, both the Law Society and the Howard League for Penal Reform launched campaigns to abolish the dock in the 1960s and 1970s, drawing on arguments about fairness and due process. They were unable to achieve any legislative change, in part because of an increasing emphasis on security. The secure glassed-in dock has raised further alarm bells, with a Judge in Australia ordering them removed from his court during a high-profile terrorism trial because he believed that they added a ‘layer of prejudice’ to the proceedings (full details about this case can be found here.)

Finally, the European Court of Human Rights has heard cases arguing that both glass and metal docks violate the prohibition on degrading treatment enshrined in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Most recently, in the 2014 case of Svinarenko and Slyadnev v Russia, the defendants claimed that their containment in a dock surrounded by metal bars was akin to being ‘a monkey in a zoo.’ The Grand Chamber of the ECtHR ruled that the ‘objectively degrading nature’ of caged docks are ‘incompatible with the standards of civilised behaviour that are the hallmark of a democratic society.’

Each of the arguments outlined above rely on legal opinion in making the case against the dock. That is, they rely on what judges think the accused might experience. In the next section, I discuss social science research that empirically examines the placement of the accused at trial.

Empirical research

In 2014 my research collaborators and I conducted an experiment testing the second of the above arguments – that the dock undermines the presumption of innocence. This was funded by the Australian Research Council in partnership with the New South Wales Department of Justice and the Western Australia Department of the Attorney General. We used a real criminal courtroom in Sydney to simulate a terrorism trial – it was the very same courtroom and with similar evidence that the Australian judge discussed in the previous section presided over. We brought in jury-eligible Australian citizens to act as mock-jurors in our trial. Professional actors played the role of judge, prosecutor, defence, accused, and witnesses. After each trial jurors retired to deliberate and then vote on a verdict.

We repeated this trial many times so that in the end, over 400 mock-jurors were able to take part. Each time, the trial was exactly the same – same evidence, same testimony, same actors, spoken in the same way. The only thing that was different was that 1/3 of the time the accused was placed in a traditional dock open to the public, 1/3 of the time he was placed behind glass in a secure dock, and 1/3 of the time he was with his lawyer at the bar table. The strength of this design is that if there is a difference between groups in terms of how jurors voted, we could be reasonably sure that this was due to the location of the accused.

Our results support the hypothesis that the dock is prejudicial. Jurors who saw the accused sit at the bar table voted guilty 33% of the time. When he sat in an open dock jurors reached a verdict of guilty 47% of the time and in the secure dock 46% of the time. There is no statistically significant difference in findings of guilt between the open and secure dock, but there is a statistically significant difference between the bar table and either of the docks. That is, any isolation of the accused seems to be prejudicial. Again, because everything else about the trial was exactly the same, we can feel confident that this difference in verdict is due to the impact of the dock.

Courts of the future?

We were surprised to find that both the open dock and the secure dock were equally prejudicial. Given this finding, along with the European Court of Human Rights’ jurisprudence about participation and dignity, we think that docks should no longer be used at trial. In 2015, JUSTICE published a report on the dock, drawing on our research to make this same case.

A likely challenge to our proposal is that docks are needed to ensure security at court. We argue that Scandinavian courts and American courts experience significant security risks, and yet they manage without docks (and, contrary to popular belief, most American courts are not full of armed police officers). Courts are already undergoing a massive change and courts of the future are likely to be flexible spaces that serve multiple functions and rely heavily on technology for communication, administration, and evidence presentation. We suggest that sound design principles and enhanced technology (for instance, to enable high-quality remote participation for parties) can ensure that courts remain safe, dignified, fair, and dock-free.

Further information

A formal research paper will be published shortly – check back here.

Wearing prison uniform in court has also been criticised and banned in many jurisdictions for its prejudicial effects on a fair trial. See a recent blog on this subject.

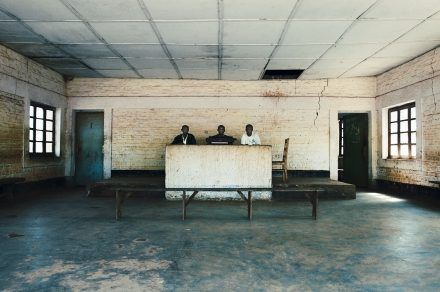

Photo: Nathalie Mohadjer, courtroom in Burundi. With kind permission.