Women in Cambodian prisons: The challenges of caring for their children

4th November 2019

In this blog, Billy Gorter from the organisation, This Life Cambodia, shares the findings of research undertaken on Why Children Accompany Women into Prison. It is particularly timely as the Global Study on Children Deprived of their Liberty is soon to be published in full, in the same week that the international community will mark the 30th anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. From data gathered from a range of official statistics, the Global Study estimated that the number of children living in prisons with their primary caregivers is 19,000 children per year.

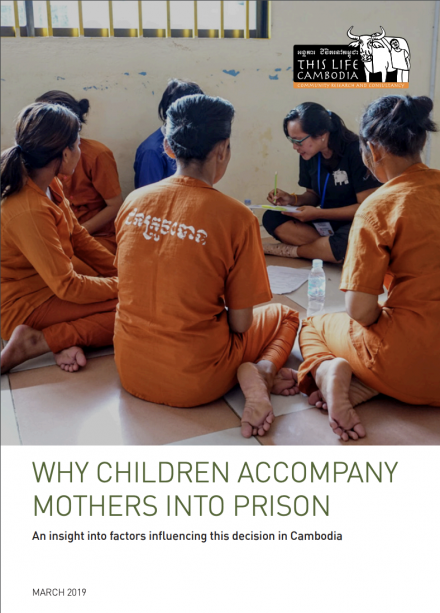

Women in Cambodian prisons, like women in prisons around the world, face particular challenges whilst incarcerated. At This Life Cambodia, we have targeted programs to women prisoners and their families whilst incarcerated and upon release. We have also recently conducted research on women prisoners with children to provide insight into the underlying causes which impact a mother’s decision to have her children accompany her to prison.

Some Background Information

While the number of women in Cambodian prisons is relatively small – they make up about 8.6% of Cambodia’s total prison population – this percentage is rapidly increasing, as it is worldwide.

In Cambodia, women in prison are likely to be first time offenders, on pre-trial detention for longer, and are more likely to receive harsher sentences for less serious offences. Most women are detained on drug or drug-related offences, many being minor in nature such as drug use. Most of the female prison population come from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds, with many having low education and literacy levels.

At a meeting of the National Council of Cambodia for Women on 18 February 2019, Prime Minister Hun Sen noted the need to speed up trial procedures, reduce sentences, and consider suspended sentencing for female prisoners who are single mothers. Prime Minister Hun Sen also announced the establishment of a legal aid team comprised of voluntary lawyers who would help to defend women who could not afford legal representation.

The children of mothers in prison

In Cambodia, children can accompany their mother in prison until the age of three. There is no standardised process for this to occur, and it is often at the discretion of the Prison Director. Conditions for children within the prison are poor, with a lack of appropriate nutrition, health care and stimulation. Often, children will stay beyond the age of three due to a lack of planning and options for the child’s care while the mother is in prison. In February 2019, according to a Ministry of Interior there were around 170 mothers with children and 51 pregnant women in Cambodian prisons.

During sentencing, judges are required to consider the personal circumstances of a suspect before ordering pre-trial detention. This includes if the suspect is pregnant or has young children, which is required by the UN Bangkok Rules on women prisoners. The pervasive use of pre-trial detention means that when mothers are unable or unwilling to have their children accompany them in prison, thousands of children are unnecessarily removed from their mothers. Cambodia’s Code of Criminal Procedure states that pretrial detention should only be ordered exceptionally (which is the principle of the UN Tokyo Rules on non-custodial measures) and only in cases of a felony or a misdemeanor involving punishment of one year or more. Ministry of Justice guidelines categorically state that investigating judges should always ask for all the relevant information about the charged person before deciding whether or not to order pre-trial detention. The guidelines are also clear that if a woman is pregnant, or if she has children and there are no suitable alternative care arrangements, pretrial detention should not be imposed unless absolutely necessary.

Our Research – Why Children Accompany Mothers into Prison

International standards require the best interests of the child to be taken into account in any decision that affects them; this excessive use of pretrial detention of mothers ignores this. In Cambodia, we have seen that decisions regarding the care of the children of prisoners are often made in an ad hoc manner with little regard to the developmental needs of the child.

Often, women do not receive adequate advice about the options they have for their child’s care, or there are other external or personal factors influencing their decision. Our research sought to examine what factors influence a mother’s decision to keep her child with her in prison. By uncovering some of these factors and considering alternative options for care or sentencing, women in conflict with the law can be better supported to make informed decisions, ensuring the best interests of their child are met.

36 women at Siem Reap prison were involved in our research – 19 had children living outside of prison (Group A) and 17 had children in prison with them (Group B). Data was collected through two quantitative surveys – one for women whose children were with them in prison, and one for women whose children were not with them in prison. Qualitative interviews were conducted with four women to complement the core data. The interviews aimed to provide a deeper insight into women’s family circumstances and experiences.

There is no standardised process in Cambodia by which women can choose whether or not to have their children accompany them in prison, but this decision is usually made at or shortly after the arrest. Of the women in Group A, almost half said their children were living with them at the time of the arrest. For Group B, the majority had their children living with them. Some women in Group B had multiple children and reported that some were living with them while others were not.

At the time of their arrest, most women in Group A reported that their children were not with them, while most women in Group B noted that their child was with them. When asked what had happened to their children immediately after they were arrested, most of the women in Group A noted that their children were initially cared for by their families. Other situations included children also being arrested with their mothers, being left with neighbours, strangers, or by themselves. For Group B, most of the women had their children accompany them immediately after their arrest. Where they had multiple children, older children were sent to stay with family.

At the time of arrest, women reported that either family, friends, colleagues, neighbours, local authority personnel, other adults, children or a combination of these people were present.

When it came to their children’s care during imprisonment, most of the women reported that they made this decision on their own. For some, there was no choice as they were pregnant at the time. Other people involved in the decision-making process were mothers, parents, and husbands.

Women in Group B noted that various people had advised them of the option to have their children accompany them to prison including prison officers, police and a lawyer. Three were pregnant and some did not know who had advised them. When asked who they discussed their child’s care with post-arrest, most women in Group A discussed with their family while most women in Group B discussed with no-one.

Our research found that both community or external factors and personal or family factors can influence women’s decision-making around whether their child should accompany them to prison or not. External factors included: access to legal advice; social norms, including community perceptions around imprisonment; access to a trusted support network that can provide alternative care options; and the (perhaps legitimate) belief that a child may have more opportunities if they do not stay in prison, such as access to education. Personal factors included: whether a woman was pregnant at the time; the age of the child; the presence or absence of family or other support structures to assist with looking after the child; a lack of financial resources; and the belief that the mother could provide better care for their child even if they were in prison.

Our research recommends that non-custodial sentencing options should be pursued where possible, particularly if the offence committed is not of a violent or otherwise serious nature.

This is based on the UN Bangkok Rules which require, in Rule 58, ‘women offenders shall not be separated from their families and communities without due consideration being given to their backgrounds and family ties. Alternative ways of managing women who commit offences, such as diversionary measures and pretrial and sentencing alternatives, shall be implemented wherever appropriate and possible.’ Where a custodial sentence is deemed absolutely necessary, women should receive accurate and timely information about childcare options and the opportunity to discuss these options with trusted support networks. Community outreach programs may assist to reduce the stigma of imprisonment, increase community understanding of the underlying factors that lead to imprisonment, and create a support network outside of prison that can assist during the sentence as well as after. Furthermore, law enforcement staff need further training to understand the specific needs of children accompanying their mothers to prison.

Our work dedicated to supporting women prisoners

This Life Cambodia’s ‘This Life in Family’ program works with incarcerated caregivers, and their families in preparation for the return of the caregiver to the family. We help primary caregivers, usually women, to maintain regular contact with their family through family tracing services, prison visits, and supporting children to remain in appropriate family care.

Outside of prison, ‘This Life in Family’ works with families to create a stable family environment for women to return to: children are given the means to continue their schooling; arrangements are made, usually with extended family, to ensure that children do not end up in institutional care; families are given support to develop income generating activities. Knowing that their children are cared for, and their families are being supported can make the prison experience a lot more bearable for women, and can increase the likelihood of successful reintegration into their family and broader community.

‘This Life in Family’ continues to provide post release support and planning to families. The program aims to bolster the resilience and capacity of families, especially during the vital stages of reintegrating a primary caregiver back into their community upon release from prison, and to enable the family to become self-supporting.

This ‘Life in Family’ was viewed as an example of best practice for the rehabilitation and reintegration of female prisoners in our region, in Penal Reform International (PRI) and Thailand Institute of Justice (TIJ)’s Guidelines “The Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Women Prisoners: Implementation of the Bangkok Rules” and at a recent expert meeting convened by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime in September 2019. By sharing This Life Cambodia’s knowledge, experience and research with respect to women prisoners and their children we hope that other organisations and countries around the world can better tailor their rehabilitation and reintegration programs to suit the specific needs and challenges of female prisoners.

This Life Cambodia’s ‘Why Children Accompany Women into Prison’ research can be found here.

More Information

PRI has developed a comprehensive toolbox to assist in the implementation of the UN Bangkok Rules in partnership with the Thailand Institute of Justice. For a more detailed examination of current trends affecting women in the criminal justice system please see our Global Prison Trends 2019 which includes a special focus on women’s healthcare in prison. Additionally, to keep updated on current developments in women’s imprisonment internationally subscribe to our quarterly newsletter: Bangkok Rules Newsletter on women in the criminal justice system.