UNGASS on Drugs: on expectations, coherence and sustainable development

4th May 2016

The UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs (UNGASS) took place New York on 19-21 April. Javier Sagredo is Regional Democratic Governance and Citizen Security Advisor for Latin America and the Caribbean for the UN Development Programme (UNDP). In this expert blog for PRI, he examines whether the outcomes of this UNGASS meeting, as well as the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), provide sufficient basis for States to start to address the many harmful consequences of current drug policies.

Conventional wisdom states that the one of the secrets of happiness in life is to manage our expectations to avoid unnecessary disappointments, while striving to change those aspects of reality that we dislike.

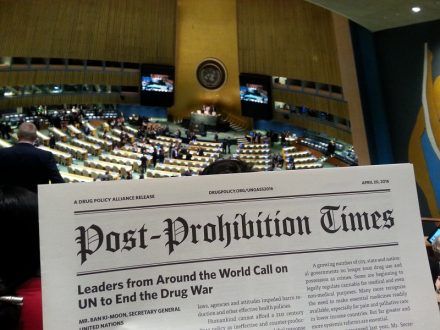

The 2016 special session of the United Nations General Assembly on drugs (UNGASS) was convened in New York during the past month of April, and like the previous ones, has delivered an outcome document that perfectly corresponds with the limited possibilities of reaching a meaningful universal consensus on an issue as complex as life itself. A “decaffeinated” end-product based on the lowest common denominator cannot leave everyone satisfied, especially those who had high hopes for either a major or even a modest reform of the international drug control framework.

Many of the actors who have actively participated in the discussion process towards UNGASS agree that the most important results lie in the process of the debate itself and in the active participation of new stakeholders, mainly those communities, groups and populations most affected by the implementation of drug policies emanating from the international regime. Moreover, this debate has allowed for the growing emergence of evidence and increased awareness and preoccupation about the negative consequences (“unintended” is not a valid euphemism) of the implementation of present drug policies.

In response to demands for the further involvement of a wider number of UN bodies in the UNGASS process, the UN Development Program (UNDP) presented, for the first time, as other Agencies and programs also did, an initial “discussion document” that displayed wide evidence on the negative impacts of drug policy on human development objectives, like poverty and inequality reduction, health, human rights, economic development, women’s empowerment, governance and the rule of law, environment, indigenous and traditional practices. This was supplemented by evidence provided by civil society, academia and even governments, as UNGASS approached.

The interpretation of the international drug conventions through national policies and legal frameworks, many of them hooked on social representations of fear, disease, deviation and crime, has done, in many cases, more harm than good. Under the “World without drugs, Yes we can!!” motto, and policy implementation through hegemonic approaches based on repression, social exclusion and abstinence, the effects have been extremely blistering for many territories, communities and individuals affected by the dynamics of the war on drugs. And, within this traditional framework, little emphasis has been placed on closing the cycle of recovery within the spheres of both health or crime, converting our prisons or “treatment centers”, for many, into dark holes of abuse without any hope for “reintegration” in a society where they were never included. Caring for those connected to drugs (users, couriers, poor farmers or small dealers) offers no added value to many politicians who respond oversensitively to electoral demands for additional security with “penal pornography” solutions. (A term coined by the French sociologist Loïc Wacquant, due to its repetitive, mechanical, uniform and predictable measures “for the express purpose of being exhibited and seen”.) This process has generated enormous costs and overwhelming difficulties for our justice and prison systems, as well as an increase in deaths, violence, disease, human rights abuses and a huge load of despair and suffering for those trapped within this cycle.

If we add to this equation the existence in many of the countries affected by drug related problems of: huge structural vulnerabilities, including lack of political will, which do not allow for the economic and social inclusion of huge percentages of the population, as well as weak governance and State presence, the existence of authoritarian police or military forces, or even armed conflict, we have the perfect conditions for a storm.

Last September, also in New York, all UN member States approved the new 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, as a complex blueprint for global action for our near future with 17 interconnected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets; a global consensus on development priorities that needs to be contextualized and adapted to each country, territory and community. The overlap of this process with the discussion for UNGASS has created a historic opportunity to identify a compass to orientate the discussion on drugs. And also a wonderful possibility to open the necessary political space that the search for new solutions requires. Something that could be drawn upon by those countries willing to improve their drug policy and their human development impact.

Under the basic principle of “doing no harm” and with the aim of accelerating development objectives, many governments need to start asking themselves and their societies how their public policies (economic, social, educational, health…and also drug policy!!) can be most effective in order to reach the SDGs and their goals, while focusing on people and leaving no one behind, as the 2030 Agenda insists. A profound and sincere assessment of present negative impacts of drug policy on human development should become the first step towards a meaningful, coherent and responsible reform of drug policy, as the basis for the construction of new solutions. We cannot keep focusing on objectives based on detention, incarceration, abstinence, seizing, and eradication figures, but must turn instead to those that allow people to thrive and have options. When respect for human rights, public health, quality education for all, gender equity, citizen security and reduction of violence, economic and social inclusion become our objectives, our perspectives change, as well as our incentives and our policy results. UNDP’s latest document on innovative approaches shows specific examples of new approaches trying to address those harmful consequences of drug policy, while promoting human development and generating positive impact on their people.

In its long final version, the UNGASS 2016 outcome document notes “that efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and to effectively address the world drug problem are complementary and mutually reinforcing” and calls upon members States to “consider strengthening a development perspective as part of comprehensive, integrated and balanced national drug policies and programmes”.

At the very least, this reference will allow many interested countries to explore new development-based approaches in order to put the 2030 Agenda upfront while benefiting from the “sufficient flexibility for States parties to design and implement national drug policies according to their priorities and needs” that the UNGASS discussion brought along.

Will this be enough? It depends on our expectations.

About the author

Javier Sagredo is from Spain, and before working for UNDP worked 15 years as Senior Advisor, Section Chief and Coordinator of projects in the Organization of American States (OAS) in areas like social inclusion, institutional development and public policy on drugs in Latin America and the Caribbean. He has also worked on international relations and as legal advisor for local government, academia and the private sector.

He has a Diploma in Decentralization and Local Development in Latin America from the Alberto Hurtado University (Chile), with a Master of Laws and Institutions of the European Union of the Free University of Brussels (Belgium), he holds a BA in Law from the University of Salamanca (Spain) and the University College Galway / National University of Ireland.