A ‘Double Punishment’: Placement and protection of transgender people in prison

30th September 2020

In this expert blog for PRI, Victoria Patrickson, who has studied governmental policy on the management of transgender people in prison, discusses the unique issues faced by this population and the approaches adopted by various governments.

Gender identification, housing decisions, searching arrangements, access to healthcare, violence and sexual assault are just a number of the issues that make transgender people a unique population to manage in prison. The struggles they face have long been overlooked by prison officials worldwide. However, recent decades have seen a promising influx of policies and guidelines aiming to address the management of transgender prisoners. Countries vary drastically in their approaches, but what is the best way forward for the protection and safety of transgender people in prison?

Drawing on Sykes’ (1958) celebrated analysis, the ‘pains of imprisonment’ have governed the daily lives of inmates for centuries. However, not all prisoners are equally affected by the hardships of prison life. Aspects of incarceration tend to interact with and amplify pre-existing vulnerabilities that individuals bring to prison. As a vulnerable population in society – with high risks of depression, suicide, harassment, unemployment and other adverse conditions – transgender people simultaneously face disproportionate levels of vulnerability inside prison walls.

Recent decades have witnessed a growth in advocacy for transgender rights, including calls for equality within the criminal justice system. Nevertheless, ongoing cases of suicide, physical and sexual assault demonstrate that prison systems are failing the transgender population time and time again. As underlined in Global Prison Trends 2020, the majority of EU member states lack special measures for the protection of LGBTQ people in prison, with few exemptions. Future efforts must be geared towards adequate policy and guidelines for those hit hardest by the rigid institutional regime of imprisonment, both in Europe and worldwide.

Unfortunately, when looking to international standards such as the UN’s Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the Nelson Mandela Rules, there is inadequate guidance on the protection of transgender populations detained. Except for an explicit mention in Rule 7 of the Mandela Rules which states that certain information should be gathered on admission to prison, including “precise information enabling determination of his or her unique identity, respecting his or her self-perceived gender”, the Rules are otherwise silent. Principle 9 of the Yogyakarta Principles, requires authorities to ensure that “placement in detention avoids further marginalising persons on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or subjecting them to risk of violence”, but these Principles remain largely on paper.

Prisons as Hyper-Gendered

Transgender is a term that applies to any individual with a gender identity different to their sex assigned at birth, which include those who identify as non-binary. This includes those who have undergone or are moving towards sex reassignment surgery, as well as those who have chosen to refrain from medical procedure. Due to their gender expression differing to that which was assigned at their birth transgender people pose a unique challenge to highly institutionalised environments such as prison. Not only this, but they face high levels of stigmatisation and victimisation as a result.

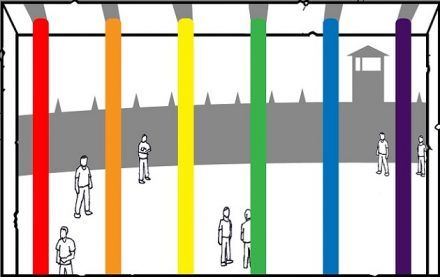

Indeed, managing transgender prisoners safely poses a unique challenge to the “hyper-gendered” world of prisons. “Hyper-gendered” signifies that the concepts of masculinity and femininity are reinforced through the structures, norms, values, roles and practices of prison staff and inmates. For instance, the majority of prison systems are built to house genders separately. By using the gender binary to make housing decisions, a ‘double punishment’ is enacted on transgender people by making their bodies hyper-visible, and thus more susceptible to violence.

By using the gender binary to make housing decisions [within the prison estate], a ‘double punishment’ is enacted on transgender people by making their bodies hyper-visible, and thus more susceptible to violence.

Housing Practices: A Global Perspective

There is a longstanding policy debate on where transgender people should be detained within the prison estate. Housing practices vary by country but the most common methods are sex-based placement, identity-based placement, and segregation.

Historically, prisoners have been housed according to their sex at birth and regardless of their gender identity, appearance, or otherwise. One of the main consequences of sex-based placement is that transgender people’s non-conformity is clear from the outset, condemning them to mistreatment from other prisoners. Although practices are changing, many prisons in Canada and a number of U.S. states still adhere to this housing approach.

Until 2004, transgender prisoners in England and Wales were persistently classified according to their sex at birth. However, the Gender Recognition Act 2004 enabled citizens with gender dysphoria to apply for a Gender Recognition Certificate with the purpose of changing their legal gender. Despite this precedent, there are ongoing reports of misplacement of transgender people in prison. In 2018, it was revealed that 97 transgender prisoners were held in male institutions in England and Wales that year, 92 of which identified as female and only two as male, indicating that male-to-female transgender people are continuously being housed irrespective of their gender identity.

In recent years, there has been a promising shift away from sex-based housing to more flexible identity-based placement. Identity-based placement is a procedure of housing in which a transgender person is housed based on the gender with which he or she self-identifies, regardless of whether they have undergone sex reassignment surgery. This practice continues to be less common than sex-based placement. Unlike in England and Wales, trans prisoners in Scotland are not required to obtain a ‘Gender Recognition Certificate’ (GRC) in order for their self-identified gender to be respected. In the US in May 2018, President Trump announced the retraction of former guidelines introduced by the Obama administration rescinding various policies that aimed to protect transgender people in prison. Trump’s new guidelines state that prisons “will use biological sex as the initial determination” for placement decisions.

In some prisons in the U.S., Canada, and England and Wales, there is also a practice of segregating transgender people by holding them in protective custody, usually in a single cell. While segregation can afford greater security, the individual is simultaneously excluded from equal participation in prison life. In addition, reduced access to education and recreational activities has been found to impact on psychological welfare/mental wellbeing.

A less common practice is to hold trans persons in special wards, allowing them to freely express their gender identity. Protected sections have been established in Italy, Brazil and England. In 2010, Italy was the first country to announce the opening of a transgender prison at Pozzale, a move welcomed by LGBTQ rights advocates. It is estimated that Italy has a total of some 60 transgender prisoners. In March 2019, England opened its first prison unit, a wing within a women’s prison for trans persons. According to official statistics from 2018, there were 139 adults in prison identifying as transgender in England and Wales. The establishment of special units, where possible, could be a means to avoid the potentially harmful resort to segregation seen in many countries. However, they too have not come without criticism.

Calls for Reform

There are several ways prison authorities can improve their housing practices and consider the individual needs of transgender people, whilst bearing in mind the safety of the wider prison population.

Firstly, classification policies need to evolve so to recognise that many transgender people live contently without sex reassignment surgery or gender-affirming certificates. Self-proclaimed gender identity should be respected, without the need for legal or medical requirements. In line with the Yogyakarta Principles, it should be ensured “that all prisoners participate in decisions regarding the place of detention appropriate to their sexual orientation and gender identity”.

Classification policies need to evolve so to recognise that many transgender people live contently without sex reassignment surgery or gender-affirming certificates.

Having said that, it is critical that housing decisions are made on a case-by-case basis with frequent review and a thorough risk assessment. Examining the situation in those countries that have opened special units for trans persons in prisons will be useful in determining whether this is an appropriate method. Policymakers may also derive benefit from comparative research; fusion of national policies could lead to a universal recommendation for the safe management of incarcerated transgender people which is much needed.

There is also a need to question the need for detention in each case, given the high-level of risk to personal safety and additional burden of time spent in prison for trans people.

The policy debate on how to house transgender persons in prison is multifaceted and complex. Above all, it is crucial that politics do not shift the focus away from the key problem that needs to be addressed: how to protect those who are vulnerable to mistreatment behind bars. It is hoped that prison institutions can adopt a more considerate and flexible approach to managing transgender prisoners, enabling them to live safely and contently in their gender identity.

Further resources

PRI/APT, LGBTI persons deprived of their liberty: a framework for preventive monitoring

Association for the Prevention of Torture, Towards the Effective Protection of LGBTI Persons Deprived of Liberty: A Monitoring Guide