Prisons and food: From in-cell eating and meal-lines to collective and domestic kitchens

2nd June 2021

People in prison lose autonomy and agency over many aspects of their lives, usually including food production and consumption. In this blog, Sabrina Puddu examines the different approaches taken to food in prisons, looking at trends from eating alone in cells, to dining halls, and collective and domestic style kitchens.

Collective kitchens are witnessing a new resurgence in society, especially in experiments of cooperative living and neighborhood community kitchens. Neither inside the canteen of an institution nor in a private restaurant, their unusual locations and arrangements of space and furniture favor new rituals of convivial banqueting and cooking, whilst supporting alternative logistics of food production, distribution, and consumption. Moving beyond the private (family) kitchen, they are said to challenge and destabilize established ideas of the domestic and to hint at emancipatory processes for women and socially disadvantaged classes. A growing number of cooperatives, NGOs and grassroot organizations implement collective kitchens in practice hence also questioning traditional forms of communal, yet top-down, catering by public institutions.

So, what about prison kitchens and the space in which food is prepared, consumed, and distributed in detention? A recurrent trend in every allegedly progressive prison facility like small-scale prison houses – by which I include a range of homely-like facilities such as transition, half-way, youth, and detention houses – sees them spotlighting the kitchen, usually labeled as ‘domestic’ and freely accessible for group or individual self-catering, as flagship of their different ethos from the traditional prison.

food is an essential element in our lives as a basic survival necessity and as trigger of both everyday and exceptional ritual practices

There is general agreement, in the social sciences, that food is an essential element in our lives as a basic survival necessity and as trigger of both everyday and exceptional ritual practices – as much in free society as in prison. Food in prison is used – and not without conflict – to negotiate relationships, identity, power, and sometimes also to establish hierarchies, nurtured by or in contrast to the institutional food logistics.

When Royal Engineer Joshua Jebb, in the 1840s, drew up the floorplans for the construction of Pentonville Prison in London, he put particular care in detailing food logistics. He conceived of the kitchen as hidden infrastructure located in the basement of the prison, in proximity to the storage areas and to the way of access from the outside. The space was carefully separated from the other functions, yet the flow of food between the kitchen and the cell was guaranteed by technological means. Meals were distributed from the kitchen to the upper floors and galleries using a hoisting apparatus and a system of trays, small wagons, and light iron carriages. The final destination of the meal-line was the cell: Jebb’s drawings depict the basic provision of cutleries – a spoon, a plate, a jar, and a cup tidily arranged in an open shelf hanging at the corner of the cell – to serve the solitary, physiological, act of eating. This project reduced food practices to a mere matter of logistic and the detained person to a consumer with no agency over their own nutrition.

Pentonville influenced the design of many modern prisons in Europe. Today, logistics of prison food keep being object of design and protocols, and on signaling the ideals of care, welfare, and progressivism of the carceral institution. These vary according to countries and according to the prison regime and security level.

Dining rooms only exist for the staff, often catered by a different kitchen and with a different menu.

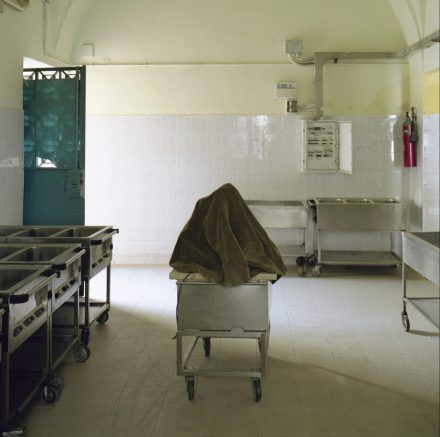

In Italian prisons, the kitchen continues to be a peripheral space outside the main wards and hidden from the eaters’ view, accessible only to a selected – imprisoned – labor force. Dining rooms for prisoners are mostly inexistent, even in open regimes, and food is delivered to and consumed inside the cell. Dining rooms only exist for the staff, often catered by a different kitchen and with a different menu. Institutional food is often supplemented by that cooked in the cell, using (legally) a camping gas stove. A corner of the cell, usually the one around the sink, is informally arranged as a kitchenette, with the little stove, utensils hanging from the wall and plastic kitchen tablecloth used as backsplash.

Dining rooms are common in other countries, where they perform the role of spaces of association. In a medium-security facility I visited in California in 2014, a large and dark dining area was adjacent to a central kitchen. Yet, there was no visual connection among the two to the point that serving was blind: a screen was built to prevent the server from seeing the receiver on the other side. A different arrangement was secured in what at the time was the main target of my visit: the California Conservation Camps, a network of rural, small, low-security detention facilities where food is considered a main perk for those that decide to ‘voluntarily’ join the program. The food area in the camps is usually a small independent pavilion comprising a kitchen open to a dining area. Here detained people eat in large tables – usually fixed at the floor with non-movable chairs – together with their working crew of peers and staff. There is no possibility for them to cook in the dormitories, with their personal locker storing just pre-packed snacks. A key area of the camp – advertised by the staff at any of my visits – is an open-air picnic and barbeque spot that is used for visits, with families allowed to bring in food.

At Ruiselede prison, an open regime facility in the Belgian countryside, a central kitchen prepares food for detained people and staff. The kitchen is opened to a bright dining room, with large tables, that people can access only at mealtime. Yet, a row of forty locked little fridges containing extra personal food provision is arranged along a corridor in the open regime area, where the people in prison can freely access a kitchenette for independent cooking. This is a little room with L-shape white cabinets and no table, targeting individual cooking.

food-groups are also a key social entity in prison life crystalizing roles and hierarchical relationships

At Pension Skejby, a Danish prison half-way house, the food area is a long room overlooking the garden and composed by an enfilade of four kitchen blocks. The twenty-six residents, a mix of imprisoned and free citizens, are in fact divided in four teams, each with an assigned kitchen block and a joint economy. Skejby seems to institutionalize the informal and self-managed food-groups that exist in most Danish prisons, where self-cooking is allowed in communal kitchens inside the housing wards and food can be purchased in little supermarkets. Born as spontaneous alliances among detained people to manage self-catering, distributing labor and pooling food resources, food-groups are also a key social entity in prison life crystalizing roles and hierarchical relationships.

These brief descriptions are far from being exhaustive but make clear how food logistics and the spatial qualities of the kitchen and dining areas are a clue of the prison regime and security level. Just to provide definite proof of this, we could look at the pictures and drawings of the Diagrama Foundation’s youth facility in Castilla la Mancha Spain, recently published by Local Time in the pamphlet ‘Design guide for small scale local facilities’. The Diagrama model wants young people proceeding across five stages, from ‘Introduction’ to final ‘Autonomy’, with each stage corresponding to a specific spatial arrangement. What immediately catches our attention when comparing the Introduction and Autonomy units is the food area. In the former, the food area is fitted with just a table and chairs, hence only eating seems possible here with food catered by the institution. In the latter, the young people are expected to do the cooking – and the cleaning – in what Local Time positively labels ‘domestic kitchen’: a fully fitted kitchen with L-shape white cabinets and backsplash azulejo-like tiles, with an adjacent dining table.

The inclusion of a ‘domestic’ kitchen is a constant in proposals for small-scale prison houses, and a flag to detach their ethic and philosophy from that of canonical prisons. A recent movement that promotes the reduction of the current prison system and its substitution with a network of small-scale integrated and differentiated detention houses is supported in Europe by the NGO Rescaled, the international spin-off of the Belgian NGO De Huizen – The Houses. Their concept finds its roots in the late-1960s proposals to restructure large institutions according to the principle of ‘normalization’ and in the few existing small-scale facilities – like the prison houses in the Netherlands or in Scandinavian countries. It goes without saying that the kitchen is the queen room in such facilities.

the kitchen is a ‘place to gain independence’; a ‘learning spot’ where an essential skill for normal life (cooking) is acquired

Two transition houses – a partial translation of De Huizen’s proposal – recently opened in Belgium, one in Mechelen and one in Enghien, with highly celebrated kitchens where the then Ministry of Justice was interviewed by national televisions. In Mechelen, the kitchen is located at the core of the house and again furnished with ‘domestic-like’ c-shaped white cabinets, where residents, in pairs, prepare food for the whole community. In a conversation with the coordinator of the transition house in November 2020, they elaborated on the multifaced role of the kitchen in the house: the kitchen is a ‘place to gain independence’; a ‘learning spot’ where an essential skill for normal life (cooking) is acquired, often through exchange and exemplarity; a ‘place of care for yourself and the others’, and of ‘collective living’.

Attempts to break the Pentonville food-logistics-line and the alienation of people in prison from food production and agency have led to a celebration of the kitchen in the small prison houses. Here, the ‘domestic’ kitchen sets the stage for collective – yet choreographed – rituals that unfold around food preparation and consumption.

This trend towards self-catering, in its good intentions, cannot but fetishize the ‘domestic’ family kitchen – the same that the free collective kitchens I described at the beginning attempted to question. Sometimes, it seems to forget to acknowledge, in an urgency to normalize prison life and making prisons homely, that the domestic kitchen is an ambiguous slippery space, where pleasures can be easily transfigured into burdens, and self-agency into yet other forms of exploitative and alienated practices. If this is a dilemma in free society, I don’t see how this can be any better in places of detention and inside the very institution that seems to transfigure everything that it absorbs.

Read more:

Godderis, Rebecca. ‘Food for Thought: An Analysis of Power and Identity in Prison Food Narratives’. Berkeley Journal of Sociology 50 (2006): 61–75.

Hayden, Dolores. The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Nieghborhoods, and Cities. 2nd pr. Cambridge: MIT press, 1981.

Illich, Ivan. Tools for Conviviality. Perennial Library P308. New York (N.Y.): Harper and Row, 1973.

Jebb, Joshua. ‘Report of the Surveyor-General of Prisons on the Construction, Ventilation, and Details of Pentonville Prison, 1844’. London, 1844. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ntxzjxny.

Kjaer Minke, Linda. ‘Cooking in Prison – from Crook to Cook’. International Journal of Prisoner Health 10, no. 4 (2014): 228–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-09-2013-0044.

Puddu, Sabrina. ‘Conservation Camps. Carceral Labor in California’. The Funambulist. Politics of Space and Bodies, no. 4 (April 2016): 40–45.

Puigjaner, Anna. ‘Bringing the Kitchen Out of the House’. E-Flux Architecture (blog), 11 February 2019. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/overgrowth/221624/bringing-the-kitchen-out-of-the-house/.

———. ‘Kitchenless City: El Waldorf Astoria, Apartamentos Con Servicios Domesticos Colectivos En Nueva York 1871-1929’, 2014.

Vanhouche, An-Sofie, and Kristel Beyens. ‘Prison Foodways. International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives’. Special Issue Appetite (2020).

Photo credit: Giaime Meloni, 2015