Prison education: university partnerships paving the way to successful reintegration

9th January 2018

Educational programmes in prison are ‘generally considered to have an impact on recidivism, reintegration and, more specifically, employment outcomes upon release’ (Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Vernor Muñoz). Nina Champion, Head of Policy at Prisoners’ Education Trust, looks at the importance of prison education and the increase in and impact of prison university partnerships around the world.

‘There is a growing recognition of the need to equip prisoners with the skills and education needed to obtain work on release’, PRI noted in its 2017 Global Prison Trends report.

I have worked at Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET) for six years influencing policy and practice. Over that time I have seen prison education rise up the English political agenda. Following a 2016 review led by Dame Sally Coates, this year governors will take control of prison education budgets, giving them the flexibility to better meet the needs of their individual populations. It is therefore a vital time to see what good practice can be learnt from overseas.

There is global political recognition of the importance of prison education, from the Doha Declaration, adopted at the UN Crime Congress in 2015, to the Council of Europe 17 recommendations adopted in 1989. This has been driven by robust evidence of the effectiveness of prison education in reducing re-offending and increasing employment. In particular, a meta-analysis published by RAND Corporation (Davies et al., 2013) in the US found:

- Prisoners who participated in education programmes had 43 per cent lower odds of re-offending than those who did not

- The odds of obtaining employment post-release among prisoners who participated in education was 13 per cent higher than the odds for those who did not

These findings were echoed in research conducted by the Ministry of Justice (2015) in England which, through analysis of data from PET, found that people supported by PET to study distance learning courses in prison, including the Open University (OU), were a quarter less likely to re-offend than a matched control group.

As part of the Steering Committee for the European Prison Education Association (EPEA), I helped to organise a recent conference held in Vienna. Coming just after the International Day of Education in Prison, the conference showcased ways in which countries are implementing the Council of Europe recommendations on prison education, from innovative arts projects to supporting foreign nationals, despite the various structural, political and resource barriers they face. A roadmap for countries to navigate those barriers is available in an excellent new publication by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

One exciting developing trend, highlighted both at the EPEA conference and in the UNODC publication (p.33 & 34), is an increase in prison university partnerships. This is particularly important given recommendations 14 and 15 of the Council of Europe state that:

- Wherever possible, prisoners should be allowed to participate in education outside prison

- Where education has to take place within the prison, the outside community should be involved as fully as possible

The findings from the RAND study (2013) provided evidence that ‘correctional education may be most effective in preventing recidivism when the programme connects inmates with the community outside the correctional facility.’

In March 2017, PET launched a network called PUPiL (Prison University Partnerships in Learning) to map, promote and support such partnerships. The same year, I was fortunate to be awarded a Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship to explore emerging and established collaborations between prisons and universities in Belgium, Denmark, Poland and California. In writing up my findings, I am developing a typology of partnership models; from prisoners and university students learning together, to lecturers teaching inside prison walls. I also found examples of university students mentoring prison learners and prisoners studying at university on day release. I witnessed these partnerships having transformative impacts on learners’ human and social capital:

‘I have learnt that it is not necessary to have the same opinions, you can look at something in different ways’, one Danish Inside Out learner explained. A Belgian prisoner said studying alongside outside students ‘made us feel more human. It is impossible to explain how much we appreciated this’.

‘I have learnt that it is not necessary to have the same opinions, you can look at something in different ways’, one Danish Inside Out learner explained. A Belgian prisoner said studying alongside outside students ‘made us feel more human. It is impossible to explain how much we appreciated this’.

In California I found out about impressive ‘pipelines’, such as Project Rebound, supporting former prisoners to access higher education and become role models and community leaders. In Denmark e-learning enabled prisoners to gain university credits and in Belgium prisoners became researchers in one partnership. University classes in criminology for prison officers in the US had a far-reaching impact on the learning culture. As one participant officer remarked: ‘What if I’m wrong? What should prison look like? I saw things differently when I walked around at work. I thought to myself it doesn’t have to be this way. The inmate doesn’t have to be the enemy.’

It’s not just in Europe and the US where such collaborations are growing. The work of the African Prison Project supports prisoners to get Law degrees in Kenya and Uganda. There is also a growing trend of prison university partnerships in Australia and South America.

Wherever you live in the world, prisons are part of our communities and most people in prison will one day be released into those communities. Colleges and universities are also part of our communities and can help successful re-entry into society. As Professor Reese, founder of the Prison Education Project that I visited, noted, there is a community college and/or university within a 30-mile radius of the majority of prisons in California. With this is mind, since 2011 Reese has mobilised 800 university student and staff volunteers to support and inspire over 5,000 prisoner learners (Reese, 2017).

A Belgian prisoner said studying alongside outside students ‘made us feel more human. It is impossible to explain how much we appreciated this’.

It is not just prisoners who benefit; in Poland, one learner who took part in a prison university partnership on the topic of Social Work told me: ‘University students read the books but real life is different. Having us in the class helped them think about the subject differently. They had stereotypes about prisoners. We wanted to show them something good. The whole project was positive for the professors, regular students and prisoner students.’

An influential report from Berkley and Stanford Universities in California (2015) concluded that ‘College has the power to change lives […] College can break the cycle of recidivism and transform formerly incarcerated individuals into community leaders and role models’. Having seen the impact of these collaborations myself, I back their recommendation that ‘Our colleges and criminal justice agencies must break out of their silos. Our policymakers must enable partnership and collaboration between the education and criminal justice fields.’

Therefore, my new year wish for prison education in England is that, with their new-found freedoms, Governors ‘break out of their silos’ to make contact with local universities and explore what collaboration could offer to staff and students on both sides of the wall.

My Fellowship report will be launched at a PET symposium on Prison University Partnerships, which will be held at the University of Westminster in London on 20th April. If you are aware of, or interested in setting up, a prison university partnership, or know of innovative prison education in your country, I would love to hear from you (nina@prisonerseducation.org.uk).

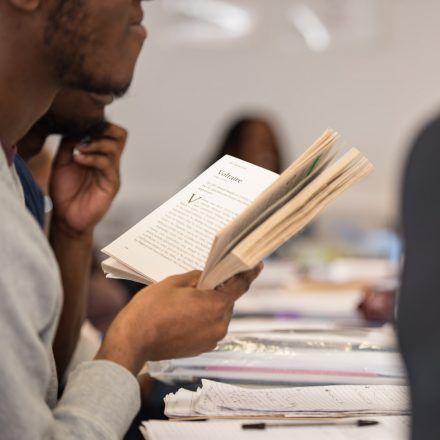

Photos: Ian Cuthbert/PET (photo taken during a prison university partnership philosophy class at HMYOI Isis with Goldsmiths University)

More information

Rule 104 of the Nelson Mandela Rules (the revised United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners) states that ‘learning opportunities should be provided to prisoners. Classes offered should be of the same level as the community education system and available to all prisoners.’ Read our short guide to the Nelson Mandela Rules here, or watch a two-minute animated introduction to the Rules.