Opening the steel door: how Colorado is reforming solitary confinement

24th July 2015

Isolation from the rest of the prison population, whether as a disciplinary measure or for the ‘protection’ of vulnerable individuals, is used in most countries to different degrees. That solitary confinement can have a terrible impact on prisoners’ mental health, is however, now increasingly acknowledged by many people. Many are also questioning the wisdom of releasing inmates who have spent long periods in isolation straight back into the community.

In the USA, some 80,000 individuals are estimated to be currently held in some form of isolation. However, a few US states have started to introduce reforms to restrict the use of segregation, among them Colorado. In this month’s expert blog for PRI, the Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Corrections – Rick Raemisch – says that the overuse of solitary confinement may itself be a risk to public safety and explains why and how Colorado has changed the rules.

I am Rick Raemisch, Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Corrections, USA. In 2011 my predecessor, Tom Clements, was hired and began reforms in the use/misuse of solitary confinement. At that time 1,500 inmates, or almost 7% of State of Colorado inmates were in solitary. Many of them were held in these cells, 23 hours per day, for years. Each year, 40% of those in solitary were released directly from solitary to the community. When I started with the Department I heard stories of correctional officers removing an inmate from solitary in leg irons and handcuffs, placing him on a public bus, removing the shackles, and then leaving him alone on the bus with the public. Ironically, in 2013 Mr. Clements was assassinated by a former inmate, who had spent seven years in solitary, and was then released directly to the community.

I was hired by Governor John Hickenlooper to continue, and complete the reforms Mr. Clements had started. We initiated aggressive programs to decrease the use of solitary confinement. We felt that we had failed in our mission. The use of solitary confinement, particularly for non-violent inmates, was primarily to run a more efficient institution. That is a noble goal, but not our mission. Our mission is public safety, and by the over use of solitary, particularly the practice of releasing individuals directly from solitary to the community, we were releasing people worse than when they entered prison. I believe that the use of solitary does not solve problems it merely suspends them. I also believe that long term solitary multiplies mental illness, and manufactures disruptive behavior. Now, our reforms have proven that the use of solitary confinement can be extremely decreased, and for the most part, used only for the violent offender.

Currently, we have approximately 150 inmates in what we now call restrictive housing, less than 1% of our population, and those individuals know when they are getting out. In the past an inmate could be placed in solitary for an indeterminate amount of time. They had to earn their way out by means of graduating to various levels. Often times if they acted up, they started over, and could spend years in solitary. Today, the maximum amount of time they spend in solitary is one year, and that is only for the most violent offenders.

Working with us, the State has passed a law that those classified as seriously mentally ill will no longer be held in solitary. We no longer release individuals directly from solitary to the community. We have developed step down programs for those in solitary to progress to general population. For the mentally ill, we have developed what we term the 10 and 10 program. Many of these individuals were previously held in solitary, and now they are held in one of two prisons that are dedicated to treating the mentally ill. The 10 and 10 program consists of a minimum of ten hours of out of cell treatment per week, and ten hours of out of cell recreation per week. The goal of course is to successfully have them re-enter general population.

Our efforts have been successful. We no longer release offenders directly from solitary to the community. Today no women are in restrictive housing, and the use of solitary as it pertains to female offenders is extremely limited. No one classified as seriously mentally ill is in solitary, and when an inmate is involved in a violation a team determines if mental illness was what caused the violation. If the answer is yes, the inmate is removed from the discipline process, and the mental illness is treated.

As a result of our reforms, inmate on inmate assaults have not gone up nor have they decreased. However, inmate on staff assaults are the lowest since 2006. Self-harm is down, and for the most part those released from solitary are not returning. We believe these reforms have led to safer institutions, and in the long run, since 97% of our inmates return to the community, it has also led to safer communities.

It is my belief that the overuse of solitary confinement in the United States for over a hundred years has not worked. It is time to change.

About the author

Rick Raemisch, who has decades of experience working in numerous areas of the criminal justice system, was appointed as Executive Director of the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC) by Governor John Hickenlooper in July 2013. Rick is recognised as a leader on prison reform and is highly sought after to participate as a subject matter expert on both the national and international level. He has testified on corrections matters before a U.S. Senate Sub-Committee involving the over use of segregation, and has participated in numerous forums on corrections at prestigious universities including Yale Law School, New York School of Law, and New York City’s John Jay College. Rick has also assisted and been a member of the US Delegation to the UN meetings in Cape Town and Vienna to re-write prisoner standards, now known as the Mandela Rules. He has authored an article in the New York Times, and has been profiled by them.

Further information

‘My night in solitary’ (20 February 2014), New York Times article by Rick Raemisch after spending a night in administrative segregation.

‘After 20 hours in solitary, Colorado’s Prisons Chief Wins Praise’, New York Times 14 March 2014.

Read more about the practice of and standards relating to solitary confinement worldwide.

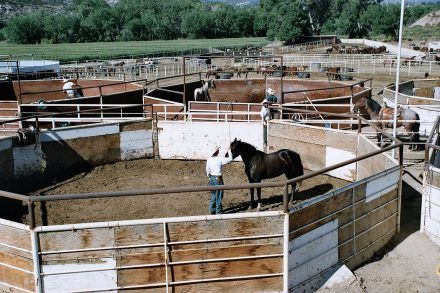

Photo: Wild Horse Inmate Programme, Colorado.