Life imprisonment: A practice in desperate need of reform

11th June 2018

At the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in May 2018, Olivia Rope, PRI’s Policy and Programme Manager, called on the UN and its member states to address the global increase in life sentences and their implementation. In this blog, based on Olivia’s speech, Katie Reade summarises the causes of the current crisis, its ramifications for the human rights of prisoners and PRI’s recommendations as outlined in its recently published policy briefing with the University of Nottingham.

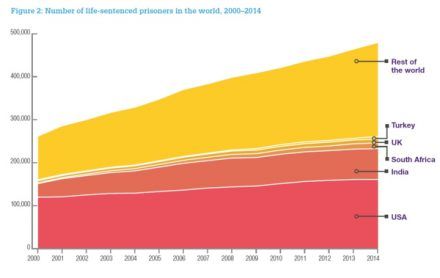

Today, an estimated half a million people are serving life sentences. Life imprisonment exists in 183 out of 216 countries and territories, and, between the years 2000 and 2014, there was an increase of almost 84 per cent in the number of those serving formal life sentences worldwide.1

This sentence, which can give the state the power to detain a person until they die, is unnecessarily punitive and often disproportionately used for low-level, non-violent crimes. Furthermore, 64 countries impose life without parole, inflicting cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment and denying prisoners the fundamental right to hope.

‘Life in prison is a slow, torturous death. Maybe it would have been better if they had just given me the electric chair and ended my life instead of a life sentence, letting me rot away in jail. It serves no purpose. It becomes a burden on everybody.’ Testimonial from a prisoner serving life without parole.

The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) state that rehabilitation to reduce recidivism is a key purpose of imprisonment. Life imprisonment often goes directly against this aim, by removing the prospect of rehabilitation and thereby undermining the right to human dignity.

In this short video, Jennifer Turner, Human Rights Researcher from the American Civil Liberties Union, discusses the use of life sentences in the United States.

This bleak picture demands the intervention of the international community. The UN last issued a report on life imprisonment over 20 years ago, in 1994. A rethink of the application, implementation and consequences of the practice is long overdue.

The 14th UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in 2020 is the perfect opportunity to examine life imprisonment and provide recommendations on its use, in order to guide member states to a system that is compliant with international standards.

To draw attention to the issue of life imprisonment and stimulate action, PRI co-published, with the University of Nottingham, Life Imprisonment: A policy briefing, which draws on research from the Life Imprisonment Worldwide project at the University of Nottingham. The briefing includes 12 recommendations for reforming life imprisonment, based on international law and best practice, to serve as a starting point for the development of standards or guidance for UN member states. There is a real need for guidance on its application and implementation at an international level, given that the number of life-sentenced prisoners has risen by almost 84 per cent since 2000.

In many countries, the abolition of the death penalty has led to a wider net of offences being considered for life imprisonment. At least 4,820 criminal offences worldwide carry some formal type of life imprisonment as a sentence. Life imprisonment is by no means restricted to the most serious of crimes; for example, in the United States, 24 per cent of prisoners serving life without parole were convicted for non-violent offences.

The policy briefing recommends that life without parole be abolished and that other life sentences should only be used when strictly necessary to protect society and in cases where the ‘most serious crimes’ have been committed. To reduce the number of people serving life imprisonment, countries should also apply proportionate sentences and allow for more judicial discretion by removing mandatory life sentences.

‘It’s like going deep-sea diving. Going all the way down into the depths and losing your oxygen. You’re struggling to get to the top. You don’t know if you’re going to make it, but you never stop struggling.’ Testimonial from a prisoner serving life without parole.

The policy briefing advises that restrictions on the regime of life-sentenced prisoners should be based on individual risk assessments and security concerns, rather than the strength of the original sentence. The damaging effects of life imprisonment also need to be recognised and considered. The Mandela Rules clearly state that the deprivation of liberty is a punishment in itself. However, prisoners are frequently and systematically subjected to harsher treatment and segregation because of their life sentences. For example, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture has found that in some European states, life-sentenced prisoners are kept separate ‘as a rule’, are subjected to systematic handcuffing and strip searches, and are escorted from their cells with guard dogs.2

PRI also advocates for reforms to the problematic, and often arbitrary, processes of review for release. In many systems, the bodies or individuals that have the power to consider the release of offenders are subjected to political pressure or are at risk of corruption. These bodies must be independent and impartial and must base their decision in law and fair procedure. Decisions should be based on the principle of proportionality and whether continued imprisonment is legitimate within the rehabilitative purpose of detention. The three key mechanisms that are typically used to release prisoners who are sentenced to life imprisonment are the courts, the executive and the parole board, with research indicating that the courts are the mechanism that best upholds fair rights and procedural standards that are necessary for such important decisions.

Once life-sentenced prisoners are released, any conditions imposed on them must be individualised and time-limited. These conditions, including supervision, must promote rehabilitation and reintegration and must be proportionate, rather than inflict further punishment.

The policy and practice of life imprisonment are in grave need of analysis at the international level. Through the UN, the international community should use the opportunity of the 2020 Crime Congress to review the global increase of life sentences and its ramifications for both human rights and prison management.

1 Life Imprisonment: A policy briefing, p. 1, citing research carried out by Professor Dirk van Zyl Smit and Dr Catherine Appleton of the Life Imprisonment Worldwide project at the University of Nottingham. Their full findings are to be published in Life Imprisonment: A Global Human Rights Analysis (Harvard University Press, forthcoming).

2 Life Imprisonment: A policy briefing, p. 6, citing the 25th General Report of the CPT [CPT/Inf (2016) 10], para. 71.

Image: Number of life-sentenced prisoners in the world, 2000–2014, from Life Imprisonment: A policy briefing.

More information

To read more about the worldwide increase in the use of life sentences and their implementation, read PRI and the University of Nottingham’s Life Imprisonment: A policy briefing.