Judged for More Than Her Crime: A Global Study of Women Facing the Death Penalty

10th October 2018

Photo: Alice Nungu by Tom Short

Today is World Day Against the Death Penalty. To mark the day, Delphine Lourtau and Sharon Pia Hickey of the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide discuss the Center’s recent report, Judged for More Than Her Crime: A Global Study on Women Facing the Death Penalty, which found that most women are sentenced to death for the crime of murder, often in relation to the killing of family members and in a context of gender-based violence. Women who are sentenced to death are also subjected to multiple forms of gender bias, with women who are seen as violating entrenched norms of gender behaviour more likely to receive the death penalty.

Just over a week ago, on October 2, Iran executed a 24-year-old woman, Zeinab Sekaanvand, after a grossly unfair trial. Amnesty International described the news as ‘horrific’ and ‘sickening’.[1] Zeinab Sekaanvand was not only a minor at the time of her alleged offence – which means that under international law, she should have been excluded from the death penalty – she was also, like many child brides, a survivor of gender-based violence. Born into a poor and conservative family, she was married at the age of 15 to an older man who soon turned abusive and violent. She appealed to the authorities and her family to protect her from both her husband and her brother-in-law, whom she claimed had raped her repeatedly, but her pleas went unheard. When she was 17, her husband was found dead, and she confessed to the crime under police torture. At her trial hearing – when she was finally appointed a lawyer – she retracted her confession, but it was too late: the court sentenced her to death.

Stories like Zeinab Sekaanvand’s, marked by the blindness of criminal justice systems to domestic abuse, child marriage, sexual assault, and other gender-specific experiences, are not exceptions. Nevertheless, until now few scholars or advocates have examined the patterns of gender bias and intersectional discrimination that affect capital prosecutions around the world. Although there are, at a conservative estimate, at least 500 women facing capital punishment globally, women on death row have to date remained largely invisible, and have never been recognised as a distinct category of rights holders facing unique challenges in the criminal justice system. Instead, the situation of female capital defendants has been subsumed into the default male framework, further marginalising women’s needs and experiences. This lack of attention has led to a dearth of information on women under sentence of death, precluding monitoring for human rights abuses and advocacy for their redress.

The Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide, in collaboration with the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, recently published a report that aims to bridge critical gaps in our understanding of how states apply capital punishment from a gender perspective: Judged for More Than Her Crime: A Global Study on Women Facing the Death Penalty. Our study is the first to examine how and when women receive death sentences and the conditions under which they are detained on death row, with a particular focus on India, Indonesia, Jordan, Malawi, Pakistan and the United States. We concluded that gender discrimination is pervasive at all stages of capital cases, but that its operation is complex. In some cases, gender bias may operate in favour of women, and some studies, notably in the United States, have suggested that women may be less likely to receive a death sentence than men under certain circumstances. We found, however, that women who are sentenced to death are subjected to multiple forms of gender bias.

Our research indicates that women who are seen as violating entrenched norms of gender behaviour are more likely to receive the death penalty.

Our research indicates that women who are seen as violating entrenched norms of gender behaviour are more likely to receive the death penalty. If, on the other hand, their crimes can be recuperated back into the norms of femininity, then they are more likely to receive a lenient sentence. Prosecutors and courts have cast women as ‘femme fatales’ or ‘morally impure’ to justify capital sentences. In the case of Brenda Andrews, sentenced to death in the United States, the jury heard details of her alleged extramarital affairs from years before the offence, and the prosecution showed her underwear to the jury during her trial, allegedly to show that she was not behaving as a grieving widow. As an appellate judge noted, Brenda was put on trial not only for murder but for being ‘a bad wife, a bad mother, and a bad woman’. In other words, female capital defendants are judged for more than their crimes: they are judged for their transgressions of gender norms.

Although they represent a small minority of all prisoners sentenced to death – under 5 per cent on average, globally – the cases of women on death row are thus emblematic of systemic failings in the application of capital punishment. When we analysed the profile of death-sentenced women, we found striking patterns reflecting the realities of gender inequality. Most women are sentenced to death for the crime of murder, often in relation to the killing of family members and in a context of gender-based violence. In Jordan, for example, of 16 women on death row, all but one was convicted of killing a close family member who traditionally wields authority, creating the potential for abuse: a husband, a father, or a mother-in-law. Other women receive death sentences for non-violent drug offences, for which international law prohibits capital punishment. In Thailand, for instance, most women on death row, who represent around 18 per cent of the country’s prisoners under sentence of death, were convicted of drug offences. Many female drug offenders engage in drug smuggling to counteract their marginalisation and improve their socioeconomic status. A smaller number of women are sentenced to death for terrorism, adultery, witchcraft and blasphemy, under laws and practices that in some cases discriminate against women.

Across the board, most women who enter prison have been disproportionately affected by gender-based violence and harsh socio-economic deprivation. They confront intersecting forms of discrimination based on ‘gender stereotypes, stigma, harmful and patriarchal cultural norms and gender-based violence’, which, according to the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, have ‘an adverse impact on the ability of women to gain access to justice on an equal basis with men’.[2]

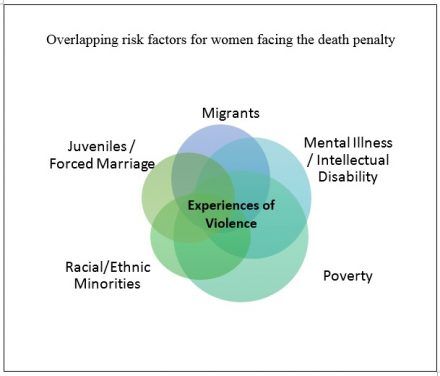

Capital prosecutions exacerbate existing inequalities and biases, including those that operate on the basis of gender. The report documents distinct risk factors for capital punishment that parallel the vulnerability of defendants, including youth, forced and/or child marriage, mental illness or intellectual disability, migrant worker status, poverty, and minority race and ethnicity. Many women on death row fall into several of these categories, compounding their vulnerability to abuse and other rights violations. Gender-based physical and sexual violence is prevalent, and most women come into contact with the criminal justice system with histories of violence and trauma, sometimes culminating in the offence for which they are charged. Women face substantial barriers in convincing a court that their actions fall within the narrow confines of ‘self-defense’. Additionally, it is extremely rare for gender-based violence to be treated as a reason to mitigate sentence,[2] despite a provision in the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules) that mandates courts to take into account gender-based violence in sentencing. Finally, illiteracy and lack of education among poor women leave them more vulnerable to discrimination, coercion, and exploitation before an offence, during interrogation, and at trial. The United Nations has documented reports of illiterate and poor women signing confessions, which they neither wrote, nor understood.

The vast majority of women on death row are indigent, which directly affects the quality of legal representation they will receive. An adequately trained and prepared lawyer remains the best defence against a capital charge, but most women who face the death penalty are unable to afford a lawyer and must rely on overstretched legal aid. Family abandonment is common for women who commit violent crimes, further reducing women’s access to economic resources for effective legal representation, or, in justice systems where financial restitution can lead to a reduction in their sentence, economic resources to compensate a victim’s family.

The release of Judged for More Than Her Crime marks the launch of the Alice Project at the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. Named after Alice Nungu, a former death row inmate in Malawi who was sentenced to death without the court ever hearing that she had suffered from years of abuse or that she had acted in self-defense, the Alice Project honours the women and girls who have suffered under legal systems blind to the discrimination and violence that have marked their lives. By telling the long-neglected stories of women on death row, the Alice Project will shed light on how gender-based discrimination plays out in countries that apply the death penalty, develop human rights strategies around the application of capital punishment to women, and invite international law to look to its own biases. It is our hope that the Alice Project marks the beginning of a new era of concern and action on the plight of women on death row.

We were encouraged that Judged for More Than Her Crime was welcomed by Special Rapporteurs and human rights experts in a joint statement given on World Day Against the Death Penalty, in which they called for governments around the world to address the situation of women and girls on death row.

Image: Alice Nungu, who was condemned to death for the killing of her husband Donald Phiri in 2003. Alice – a survivor of brutal and systematic domestic violence – was imprisoned for 12 years, before being released in 2015 after lawyers assisted by the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide presented evidence of her ill health and history of gender-based violence. Alice died just weeks after her release. Photo: © Tom Short

More information

Little empirical data exists about the crimes for which women have been sentenced to death, the circumstances of their lives before their convictions, and the conditions under which they are detained on death row. To mark the World Day Against the Death Penalty, PRI and the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide have jointly published a factsheet that focuses on the latter topic, with some introductory remarks on the profiles of women under sentence of death. The factsheet draws upon the Cornell Center’s recent report, Judged for More Than Her Crime: A Global Study on Women Facing the Death Penalty.

Endnotes:

[1] Amnesty International, Iran: Victim of domestic and sexual violence, arrested as a child, is executed after unfair trial, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/10/iran-victim-of-domestic-and-sexual-violence-arrested-as-a-child-is-executed-after-unfair-trial, Oct. 2, 2018.

[2] U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Death penalty disproportionately affects the poor, U.N. rights experts warn, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22208&LangID=E, Oct. 10, 2017.