Jailed for watching daytime TV: the need for prison reform in Africa

7th October 2015

In a recent report on over-incarceration and overcrowding, the UN Commissioner for Human Rights argued that that custodial sentences should be imposed as measures of last resort and applied proportionately to meet a pressing societal need. A recent visit to East Africa by Rob Allen illustrated that much more needs to be done if that is to be achieved in the region.

This blog was first published on Rob’s own blog, Unlocking Potential. Reposted here with kind permission.

One 22-year-old Tanzanian explained that he had been sentenced for watching television during the day. His offence seemed to be one of ‘idleness’. Although his punishment was community service, this had only been imposed after he’d spent four days in prison. Throughout Africa prison appears regularly used to punish these kind of colonial era offences or for failures to comply with contemporary government regulations whether about conducting business (such as operating a club without a licence) or obtaining fuel (such as making charcoal in the forest).

Most of the Kenyan cases we heard about involved illicit alcohol − brewing it, selling it, getting drunk on it even carrying it. A presidential decree in July urged a crackdown on so called secondary alcohol and this is being vigorously enforced by local administrators. The country has a serious problem with drinks known as Changaa or Mugacho which, when adulterated have led to deaths by poisoning, blindness, and what was described to us as a failure by men to carry out their husbandly duties. But some at least of the drinks play a role in traditional customs at weddings, parties and other gatherings.

More than a third of the 300 women (and their 50 babies) we saw in Meru prison had been committed for a failure to pay large fines imposed for alcohol-related offences of one sort or another. While many are likely to see their sentences commuted to community service through a High Court ‘Decongestion Programme’, using criminal justice to crack down on the problem has created additional hardships on those who make their living by producing it and put considerable pressure on an already overstretched prison system.

That system still suffers from the persistent problem of excessive pre-trial detention; almost 800 of the 1200 men locked up at Meru were awaiting trial. Some were charged with serious and non bailable crimes, but more than half, according to the Superintendent, were facing charges for petty offences. One barrier to their release is that magistrates worry about being thought corrupt if they free a defendant. Another is that, if they do so, the police are unwilling to pursue him should he flee. The result is unaffordable bail and routine remands in custody, sometimes for longer than any likely sentence.

Some defendants choose to bear the miserable conditions rather than change their plea, either through determination to maintain their innocence, fear of mob justice in the community, or to benefit from the limited food and shelter unavailable to them outside. Judicial reform and performance management initiatives in both Kenya and Tanzania look so far to have failed to tackle some of the underlying dysfunction in the countries’ criminal justice processes. Indeed it may have made things worse. One magistrate told us his target of completing 250 cases a year provided a disincentive to adjourn cases for a report on an offender’s suitability for an alternative sanction.

There seem to be some relatively easy prison reform wins; Kenya has no remission or parole, and Tanzania does not even subtract time spent on remand from the length of prison sentences. Taking action on these are the kind of steps the UN Commissioner wants States to take to tackle prison overcrowding so that they ‘comply with their international obligations, and guarantee detainees the dignity inherent to every human being’.

Further information

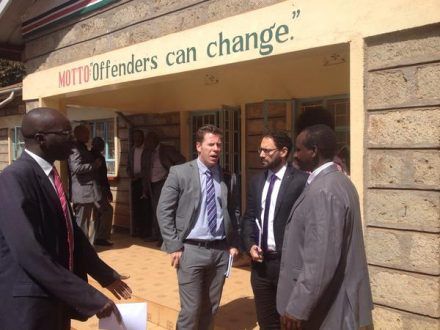

Rob was in Kenya and Tanzania to help evaluate PRI’s ExTRA (Excellence in Training on Rehabilitation in Africa) project, funded by UKAID, which aims to test a new model for effective delivery of Community Service Orders (CSOs) in three pilot regions of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

About the UN High Commissioner’s report on the causes of prison overcrowding

This is the first report by the UN Human Rights Council to address the causes of prison overcrowding. It identifies, for example, excessive recourse to pre-trial detention, lack of non-custodial alternative sentences, and disproportionate sentencing policies – and draws a clear link between over-incarceration and overcrowding and the violation of human rights.

An advance edited version of the report (UN doc: A/HRC/30/19) is available here. PRI, along with other organisations, provided input into the report. Our contribution can be found here.

See also: A blog earlier this year from Andrea Huber, PRI’s Policy Director, on why the overuse of imprisonment is a human rights issue and The fight against mass incarceration goes global by Jennifer Turner, American Civil Liberties Union, welcoming the High Commissioner’s report and its importance for US criminal justice policy.