‘Imprisonment is expensive’ – breaking down the costs and impacts globally

24th July 2020

In the third blog of our series exploring trends documented in Global Prison Trends 2020, Jeanne Hirschberger – researcher for the report – explains prison budgets. Jeanne details the levels of inadequate resourcing for prisons globally and the impact of this on the human rights of those detained.

Massive overcrowding, lack of access to healthcare, inhumane detention conditions, difficult working conditions for staff, violence, discrimination, are only a few of the issues that prisons all over the world have been facing for years, as documented in Global Prison Trends 2020. In researching for this report a common denominator I found with all prison systems (with a few exceptions) is the lack of adequate resources allocated to run these institutions smoothly; and the current context of a global pandemic, with a global economic crisis ahead, this situation may be aggravated.

Imprisonment is expensive

First of all, it is essential to recall that prison is ‘an expensive endeavour’, as put by the think-tank Prison Policy Initiative. Authorities – usually public – have to cover basic needs of people in prison, that by definition cannot provide for themselves, such as food, health care, sometimes clothing, housing and its associated running costs like building maintenance, electricity or water. There are also significant financial costs associated with safety and security, including recruitment, training and salaries for staff. Finally, adequate funding is also needed to provide a conducive environment for rehabilitation and reinsertion, through specific activities, programme and support.

Beyond those direct and easily identifiable aspects of imprisonment, there is a wide range of further ‘indirect costs’ that the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) described as ‘difficult to measure but … are immense and long-term.’ Those could include additional costs such as the ones associated with policing, bail fees or even the cost for families to have a close one in prison – such as, e.g. visitations or telephone calls. To take it even further, and even though it is almost impossible to measure, the long-lasting impacts of imprisonment on peoples’ lives, including with regard to health, personal finances, employment changes, and broader societal costs, would push the costs higher still.

Recently, the Prison Policy Initiative took up the challenge to quantify the real total cost of imprisonment in the US. It concluded that while public corrections agencies reported a total budget of US$80.7 billion for the year 2017, the actual total cost of imprisonment in the country amounted to US$182 billion a year. While this study is US-oriented, it is not difficult to imagine that the general conclusion, namely that imprisonment has a far higher cost for governments and society as a whole than the actual allocated expenditure, can be applied almost everywhere.

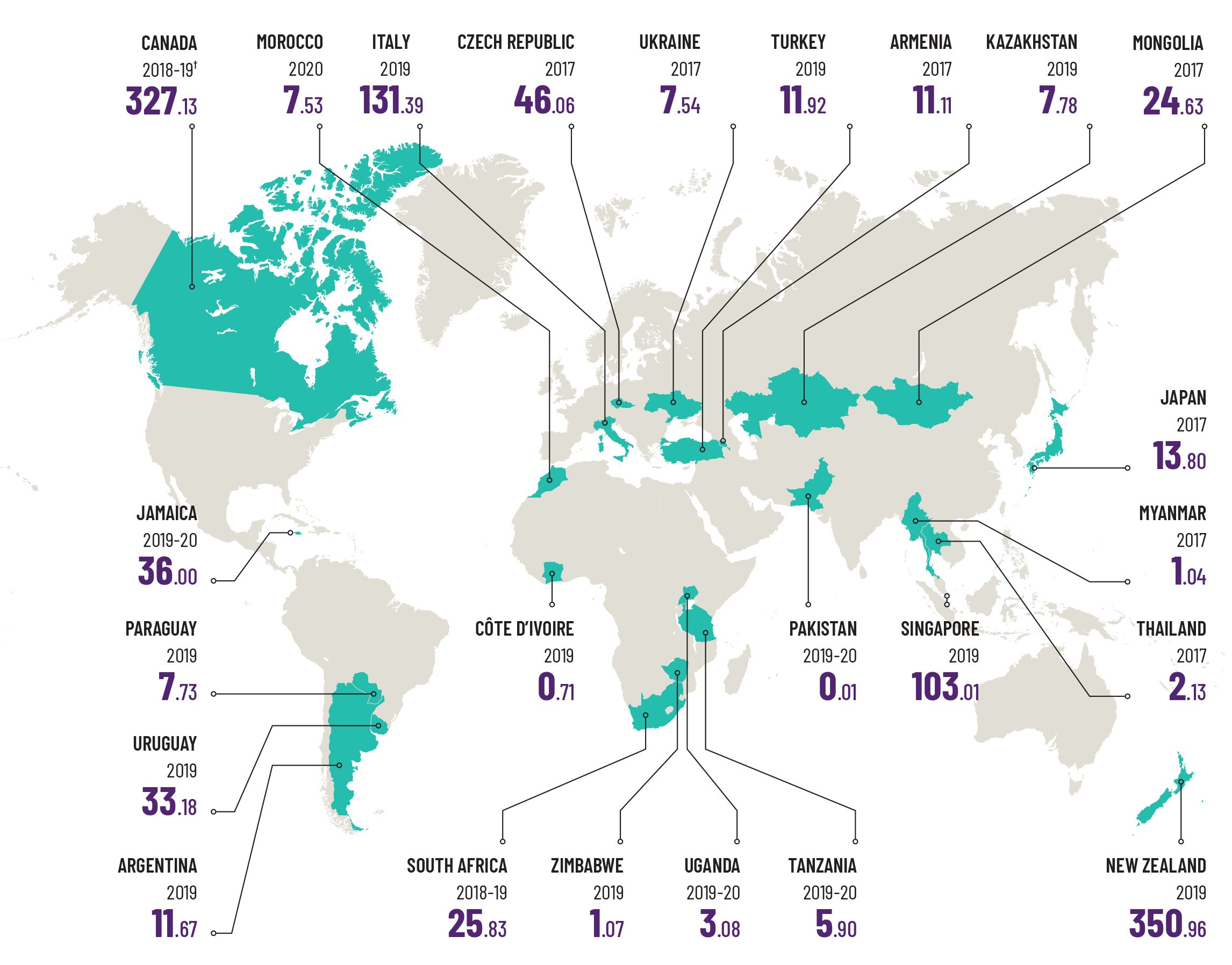

Map showing budget allocated per person in prison per day (in Euros) – see Global Prison Trends 2020, page 16 for more information.

Prisons are not a political priority

The data that we could find showed that penitentiary systems generally receive low levels of funding – there were a few exceptions, but generally this was the rule. Low funds effectively means that prisons remain a low political priority. A comparative overview of government expenditures on prisons across 54 countries shows that penitentiary budgets usually amount to less than 0.3 per cent of their gross domestic product (GDP). For instance, in 2017, the European Union (EU) 28 member states’ spending on prisons averaged 0.2 per cent of national GDP.

The data that we could find showed that penitentiary systems generally receive low levels of funding – there were a few exceptions, but generally this was the rule. Low funds effectively means that prisons remain a low political priority.

Many prison systems have so few resources that they struggle to meet basic needs such as food, healthcare, clothing and even shelter in a safe, hygienic environment. In Cambodia for example, the amount allocated for food per prisoner per day was reported to be less than EUR 1 (KHR 3500). The international poverty line set by the World Bank is of around EUR 1.70 (USD 1.90). While this standard includes more than just food costs, it does provide a basis for comparison to indicate how alarmingly low the food expenditure in some prisons can be. As a result, in many countries, authorities rely on families, charities or religious organisations to provide food, healthcare services and other essentials for people in prison.

Staff and infrastructure appear to be the main costs for prisons. In France, around 41 per cent of the penitentiary administration’s 2017 budget was dedicated to staff, administrative and operational costs. In Italy, the proportion is higher, with 76 per cent of the penitentiary administration’s 2019 budget being allocated to personnel costs. In South Africa, employee compensation and payment for buildings and other fixed structures amounted to 74 per cent of the Department of Correctional Services’ 2018-19 budget.

This is not very surprising, because buildings and personnel simply require a lot of resources, especially with so many people in prison all around the world. However, this phenomenon comes with two further issues:

First, the emphasis put on infrastructure and staff often means that there is not much left for rehabilitation and reinsertion activities and support, that are put to the background. Second, this high proportion of total funding does not necessarily mean it is efficiently used.

Despite constituting one of the most important part of prison-related expenditures in many places, infrastructure (including for hygiene) remain below standards and prison staff underpaid and overburdened. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that people are most at risk inside prison facilities, due to i.a. overcrowding in insalubrious buildings, with a lack of access to fresh air, water and to healthcare coupled to other underlying health conditions that disproportionately affect prisoners. This in turn puts the safety of prison staff at risk, lacking resources to protect themselves and the people they are guarding. Some countries thus opted for mass releases in response to outbreaks, which shows how dire the situation can be: in order to protect their lives and society as a whole, people were taken out of prison.

About data and transparency

It is difficult to quantify the amount of money spent on criminal justice systems, and specifically penitentiary systems, at the global level. One reason for this is the lack of transparency.

There are too few prison services (or their ministries) that provide readily available, clear, understandable or even recent information. The only solution, in many cases, is to search through the entire state budget, which brings several issues: the prison and criminal-justice related data and information are buried in—and sometimes scattered across—a huge amount of other information, the technicalities of the format and content makes it sometimes difficult to comprehend, the national specificities in how the budget is made and what it covers inhibits international comparisons. In other instances, information is not readily available or complete on the grounds that it is a national security matter.

The Classification of the functions of government (COFOG), an international standard classifying the purpose of government activities developed by the OECD and the UN Statistics Division, includes prisons as a component, providing a basis for international comparisons. However, it remains underused at the global level.

Lack of funding leads to human rights violations

Providing prisons with adequate funding is not about numbers and figures. It is not about marginal change. It is not about making prisons into 5-stars hotels, or even 1-star hotels! In the current context, given the situation in so many countries, it is about human rights.

Where prison budgets are not enough to cover even basic needs of the people they house, and where families and civil society cannot support them, people in prison die of malnutrition and ill-health.

Where prison budgets are not enough to provide prison and probation staff with means to achieve their mission safely and efficiently, it can have severe consequences for both people in prison and staff. Deteriorating living conditions of people in prison, coupled with degrading working conditions of staff, often lead to rising tensions, violence and ultimately deaths within prisons.

Where prison budgets are not enough to provide a conducive environment for rehabilitation, imprisonment becomes a cycle almost impossible to break, with high rates of recidivism and long-lasting impacts on people and society.

Lack of funding, to put it simply, leads to human rights violations in prisons and should be addressed as such, and not just as a mere budgetary concern. This is even more so important now with coronavirus putting people’s health and lives at risk in detention.

A way forward

Funding is not the only way to address what is described as ‘the global prison crisis’, but it is an important one, because it is inherently transversal. In most parts of the world, more resources are needed. The focus should, however, be as much on quantity than on quality. It is important that penitentiary systems receive enough funding to run smoothly. It is equally important that these resources are used adequately to protect the fundamental rights of people in prisons and to focus on reinsertion and rehabilitation, which is the primary goal of imprisonment, as set by the UN Nelson Mandela Rules.

Funding is not the only way to address what is described as ‘the global prison crisis’, but it is an important one, because it is inherently transversal.

Paradoxically, while prisons are a financial burden for many governments, imprisonment remains the primary and sometimes sole response to criminal behaviour. The consequences of mass incarceration, in this context, are logic: the more people are imprisoned, the less sustainable for countries it becomes and the more severe the human consequences are.

It is why, ultimately, the best way to reduce the high cost of prisons is to address the crisis they are facing. It is to address overcrowding and its multiple causes, in a sustainable manner that goes beyond building new prison places. It is to develop and further the use of alternatives to imprisonment, that provide a solution to global penal policy challenges, and that may prove less expensive. It is to focus on rehabilitation and reinsertion in order to break the unending cycle of imprisonment.

The COVID-19 global pandemic has shed light on the prison crisis, sometimes amplified it, and sometimes, with mass releases and a sudden more extensive use of alternatives in many places, provided a glimpse of what distancing from imprisonment as the only response to crime may look like. On all accounts, as much operationally as morally and financially, it is worth building upon.