Depopulate, Single Cell, Test: Finding the evidence base for strategies to control COVID-19 transmission in a large urban jail

15th October 2020

Over 240,000 people in prison in 110 countries have tested positive for COVID-19 to-date. Seven months after the pandemic was declared, many detention facilities around the world are still struggling to prevent and respond to outbreaks of the virus. In this expert blog, as part of PRI’s series exploring trends in Global Prison Trends 2020, five researchers in the U.S. present their findings on the effectiveness of depopulation, single cell occupancy and testing as key measures to reduce transmission in places of detention.

Across the United States (U.S.), many of the largest clusters of COVID-19 outbreaks have occurred in jails and prisons, where the built environment and activities of daily living make physical distancing impossible. High profile outbreaks include Riker’s Island Jail in New York City, and, more recently, San Quentin prison near San Francisco. Despite the severity of outbreaks in correctional facilities, US evidence-based guidelines surrounding the prevention and management of COVID-19 within such settings was delayed in publication and limited in scope. Weeks after the first major outbreaks in jails, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published interim guidance for correctional facilities to help mitigate COVID-19 transmission, which included limiting transfer of incarcerated people between facilities, restricting the number of visitors entering facilities, promoting personal hygiene and environmental sanitization, maximizing the space between those incarcerated (i.e. arranging bunks so individuals sleep head to toe), and screening staff for symptoms. Adherence to the guidelines in the US has varied. Internationally, the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe released similar recommendations to the US CDC in their interim guidance. Some non-governmental organizations, such as Penal Reform International, produced separate guidance that was broader in scope and sought to balance health and well-being with human rights.

Absent from these guidelines are three other mitigation interventions: depopulation (cessation of new detentions and release of incarcerated individuals), single celling (increasing the number of individuals in cells by themselves), and testing asymptomatic individuals. Though there was a lack of concrete evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions at the beginning of the outbreak, implementation of one or more of these interventions in correctional facilities was common as facilities scrambled to take additional measures to prevent outbreaks. Therefore, we decided to focus our recent not-yet-peer-reviewed study on estimating the effectiveness of depopulation, single celling, and asymptomatic testing to provide additional information that could guide correctional policymakers and public health agencies.

We partnered with a large urban jails in the U.S. to develop a mathematical model to represent the spread of COVID-19 using their data on both those incarcerated and staff. The model was a modified SEIR model, which included disease states of susceptible, exposed, asymptomatic infected, symptomatic infected, quarantined, hospitalized, and recovered/removed. The data included the number of new COVID-19 cases per day in the jail among staff and incarcerated people. As expected, there was large variance in the number of new cases per day, so to develop a better model, we used a technique called a moving average. The moving average allowed us to create a smoother curve to represent new cases per day. The resulting model predicted the number of new cases per day within 19% of the smoothed moving average of new cases per day.

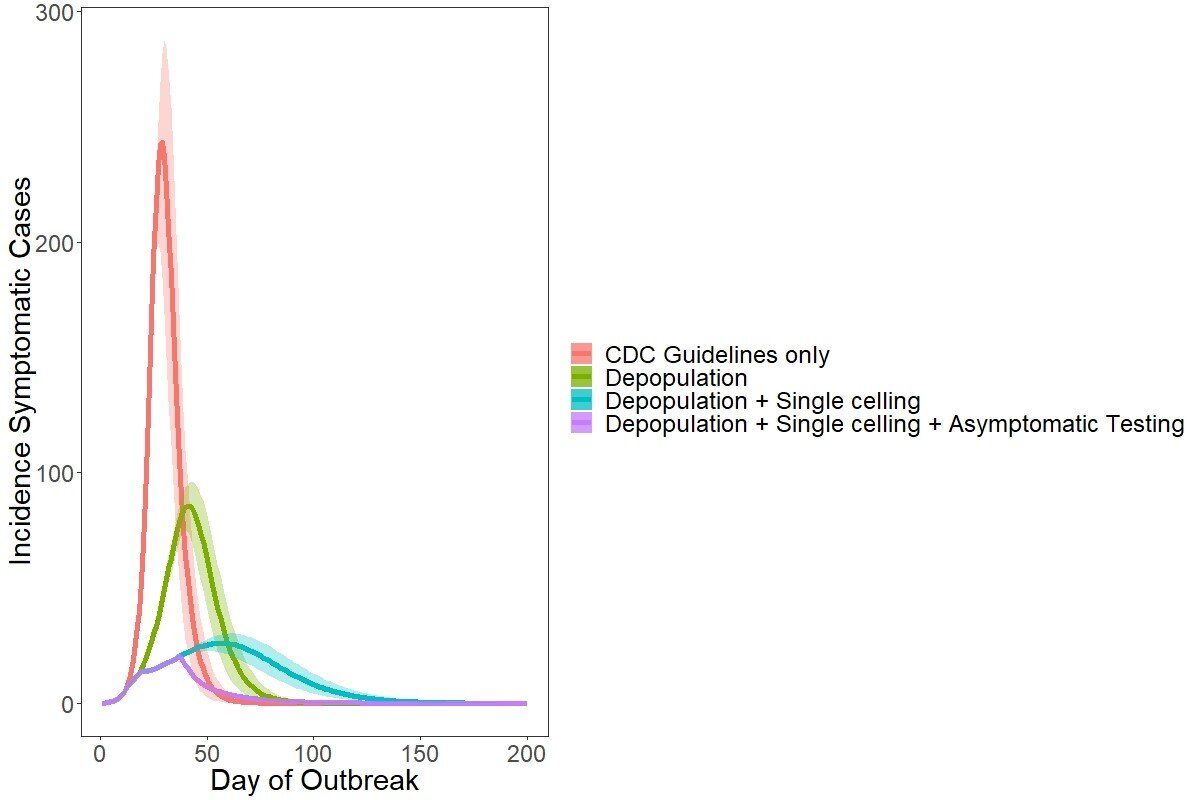

The jail implemented many proactive measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 in addition to depopulation, single celling, and asymptomatic testing. We broke their efforts into four different phases: phase 1 included the initial outbreak following only CDC guidelines, phase 2 indicated the start of depopulation efforts, phase 3 saw the increased effort of single celling, and phase 4 marked the start of asymptomatic testing. At the beginning of the outbreak, we estimated that every infected individual would infect around eight other people and depopulation efforts in phase 2, in addition to standard CDC recommended interventions, decreased transmission by 56%. This was followed by a subsequent 51% decrease in transmission during increased single celling and an additional 73% decrease in transmission with the start of asymptomatic testing. In Figure 1, you can see how these interventions “flattened the curve” of the COVID-19 outbreak within the jail with respect to symptomatic cases.

Figure 1. Projected incidence of symptomatic cases for all intervention phases (Phase 1: initial outbreak, Phase 2: depopulation began, Phase 3: increased single celling, Phase 4: widespread testing of asymptomatic incarcerated individuals).

In total, our model predicted that these additional mitigation strategies implemented by the jail, on top of standard guidance, averted as many as 3,200 symptomatic cases of COVID-19, 450 hospitalizations, and 30 deaths over 83 days of data. This is an over 80% reduction compared to the initial outbreak conditions, when CDC guidance alone was followed.

While models are not an exact science, our results indicate that depopulation, single celling, and asymptomatic testing are effective interventions at mitigating disease and morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in large jails. Depopulation can most quickly be achieved by both decreasing the number of intakes and increasing the number of releases. In the US context, this means numerous agencies and individuals have the authority to lead depopulation efforts. Police departments, judges, and, in some cases, correctional departments have the power to decrease jail admissions, while judges, lawyers, and community bail funds can assist in increasing the number of releases.

Despite incarcerated populations at recent lows, increasing access to single-occupancy cells will not be feasible without depopulation efforts as many facilities are consistently overcrowded, and as supported by our model, depopulation will not lead to a contained transmission rate alone. To be clear, single celling should not be confused with solitary confinement; rather, it is placing one person in a cell at least 6 x 9-foot area to increase physical distancing within facilities as described by a recent AMEND brief. Implementing aggressive measures to increase single celling with depopulation to combat COVID-19 in correctional facilities will require interagency coordination to achieve full effectiveness potential.

Finally, asymptomatic testing with PCR testing is a key component to COVID-19 mitigation. Our partner jail focused on asymptomatic testing through contact tracing, but questions remain about how to best implement asymptomatic testing in correctional facilities. Both national and international health agencies, such as the CDC and the World Health Organization, should address depopulation, single celling, and asymptomatic testing in future guidance for detention facilities and how best to execute these measures.

As governments across the globe focus on re-opening economies, strategies should be devised to protect those who are incarcerated and those who work in correctional facilities by further decreasing the population to ensure future outbreaks are averted. Despite flattening number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to COVID-19 in many countries, experts in the U.S., Europe, and Asia all warn of or are seeing emergence of a second wave. This is the opportune moment for interagency collaboration to support correctional facilities in getting out ahead of a second wave of cases and sure up their prevention measures. By implementing depopulation now, in a proactive manner, facilities may be able to set a precedent for mechanisms to effectively decrease intakes and increase releases. These efforts will require collaboration between law enforcement, the legal system, departments of public health and correctional facilities that is unprecedented but necessary as a pandemic response. This will also allow more facilities to implement single celling for currently incarcerated people and ideally single celling for new intakes to be separated from general populations upon arrival. Moreover, asymptomatic testing will be critical to the successful implementation of contact tracing efforts. Contact tracing is a critical component to re-opening strategies where physical distancing measures are relaxed (e.g. schools and correctional facilities) and will be a necessary endeavor to prevent future large-scale outbreaks in correctional facilities. COVID-19 has shaken the globe to its core with unprecedented spread and deaths; as we continue the uphill battle to managing this pandemic, we must continue to study and promote evidence-based mitigation measures, especially for the most vulnerable.