A global perspective on prison officer training and why it matters

23rd November 2022

Global Prison Trends 2022 highlighted severe staffing shortages in prisons and challenges shared across prison systems worldwide in maintaining adequate staffing levels. In the latest blog of our series examining trends identified in the report, Ella Töyrylä, a former prison officer in England, considers the importance of training provided for prison officers for staff retention, satisfaction, and approach to rehabilitation.

Prison officers are the backbone of prison services around the world but are often expected to conduct this challenging public service with limited training. While international standards recommend that prison officers receive both initial and continuous training throughout their careers, the discrepancy between countries is large, as officers’ education ranges from a university degree in some places to only a few weeks training in most jurisdictions. The training matters since such investment could remedy the chronic prison staff shortages that plague prison services worldwide while also enabling them to adhere to human rights standards and contribute to rehabilitation efforts; ultimately creating safer communities for all.

a balanced mixture of theory, practice and experiential knowledge

The UN Nelson Mandela Rules emphasise that the ‘prison administration shall ensure the continuous provision of in-service training courses to maintain and improve the knowledge and professional capacity of its personnel, after entering on duty and during their career’. At the regional level, the Council of Europe advises that ‘induction training curricula for newly recruited prison staff should be a balanced mixture of theory, practice and experiential knowledge, and the European Prison Rules recognise prison management’s role in enabling officers to maintain their professional skills through training and specialising in the specific cohort of people they work with. Since 1996, when the Kampala Declaration on Prison Conditions in Africa was adopted, there has been a consensus that increased staff training is a prerequisite for the competence and pride in their work that is required to improve prison conditions in the region.

Around the world, the length of prison officer training ranges from just a few weeks to multiple years, averaging around 100-300 hours. The focus and content of training also varies between jurisdictions from a security focus to an emphasis on rehabilitation. It does not seem possible to identify regional trends in prison officer training, as a variety of approaches are evident in each region. In South America, for example, Chilean prison officers undergo two academic semesters of training before commencing in post, while officers entering service in Brazil are offered a few days to a week of classroom-based training. In northern Europe, Norwegian prison officers study a university-accredited course that enables them to deliver rehabilitative services, the Swedish officer’s training is measured in weeks, taking a vocational focus, while specialist roles are equipped with enhanced training opportunities.

When exploring prison staff training, in addition to formal pre-service training, on-the-job learning is often emphasised, and some research deems ‘the process of becoming a prison officer to only really start with the recruit’s first posting’. In Nigeria, prison officers’ training emphasises the importance of observing experienced colleagues’ work and copying their behaviour. In Greece, officers train for four months before starting to work in prisons but believe the education fails to equip them to deal with the difficult situations that occur in prisons. Such experiences highlight the importance of linking the contents of formal and informal training and clarifying the on-the-job applications of the formal elements of the training.

difficulties with recruitment and maintenance of adequate staffing levels are common in prison systems

This is not to diminish the importance of formal training. Among other benefits, formal training is important for staff satisfaction as difficulties with recruitment and maintenance of adequate staffing levels are common in prison systems, and often linked to poor working conditions and inadequate pay. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights recognises that to attract and retain a professional, competent and motivated workforce, the conditions of prison officers’ service need to empower them to achieve the technical capacity for the profession. In Norway, where prison officers undertake a two-year course that can be extended to a bachelor’s degree in Correctional Studies, prison officers have reported being generally satisfied with the level of education they receive and, in line with international standards, perceive that continuous and specialised education is needed in the long-term to support staff retention and opportunities for promotion.

Enhanced training of prison officers is also vital in helping prison services worldwide to achieve the rehabilitative aims, which were reiterated in the Kyoto Declaration adopted at the UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice in 2021. Research suggests that belief in rehabilitation is strongest among well-trained and experienced officers. Furthermore, a study into the development of early prison officer cultures in Scotland proposed that while training established rehabilitative beliefs in recruits, these were countered by the often punitive organisational culture learned from colleagues upon commencing to work in the prison environment. In England, the Unlocked Graduates programme is encouraging the idea of further education for prison officers by offering recent graduates a chance to gain a master’s degree while working as prison officers. As a graduate of the scheme, I believe that the continuous training throughout the two-year programme both empowered me to apply the theory in practice and motivated me to retain a rehabilitative approach to my work. Furthermore, being surrounded by likeminded participants helped me to challenge and shift the views of other colleagues, who did not always have a rehabilitative focus in their interactions with people in prison.

prison staff training should be considered paramount

In conclusion, prison staff training should be considered paramount and a worthwhile investment; not only to comply with international standards, but also to improve staffing levels in prison that struggle to keep the staff they recruit and to increase the success of rehabilitative initiatives. Since prison staff cultures in many countries have remained largely unchanged and punitive throughout history, formal education is necessary to enable services to deliver the expected results – to release people who will not offend again. This is only possible when continuous and applicable training is considered an essential element to ensuring prisons are staffed adequately with experienced, professional officers.

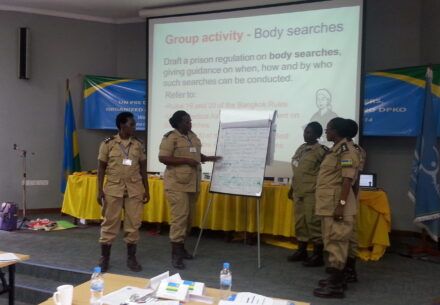

Photo: Training on the UN Bangkok Rules in Rwanda, 2014, supported by UN DPKO.