The Dutch experience: innovating practice to support foreign national prisoners

24th March 2016

Worldwide more than a half a million foreign nationals are detained abroad. While entitled to assistance under international law, in practice only a few countries provide assistance to their nationals. One of these is The Netherlands. However, uniquely, as well as assistance provided by diplomatic staff, Dutch citizens detained abroad can also receive regular visits from ex-patriate volunteers in a scheme run by the Dutch Probation Service. Femke Hofstee van der Meulen, Director of Prison Watch, evaluated the impact of the volunteer programme as her PhD. Her findings are summarised here.

In recent decades prison populations have become less homogeneous. In prisons all around the world a huge range of nationalities and languages can be found alongside cultural and religious diversity. This is particularly true for countries in the European Union, where on average nearly one in every five prisoners is a foreigner. The highest percentage can be found in the Middle East with more than one in two prisoners being a foreigner. Worldwide more than half a million foreign nationals are detained abroad.

According to the research literature, foreign national prisoners (FNPs) encounter many difficulties in daily prison life. These difficulties stem from their foreign status, language obstacles and distance from their families. They feel often socially excluded. According to the universally accepted Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, FNPs are entitled to receive consular assistance from consular staff from their country of origin. In practice only a few consular authorities provide support to their nationals detained abroad. One of these countries is the Netherlands.

Although Dutch FNPs have no right to claim consular assistance (there is no Dutch Consular Act), they can receive it in practice. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs has committed itself in Parliament to monitor the correct application of the rules by the country of detention and to monitor whether Dutch FNPs are held in humane prison conditions. Dutch FNPs can receive consular assistance from diplomatic staff, from volunteers of the International Office of the Dutch Probation Service and from chaplains of the religious organisation Epafras.

The Dutch Probation Service has 350 volunteers who live abroad and visit Dutch FNPs in their region every six weeks. Epafras has 40 chaplains from different denominations who visit Dutch FNPs once or twice per year. Besides these personal visits, Dutch FNPs also receive other kinds of consular support, such as magazines and a monthly allowance of €30 for those detained outside Europe. The central research of the PhD was whether the ‘consular assistance, as received by Dutch FNPs, contributed to their detention experience, special needs and resettlement’. In total, 584 Dutch nationals detained in 54 countries participated in the research and over 150 interviews were conducted with prisoners, ex-prisoners, consular staff, volunteers and family members of prisoners.

The study confirmed that Dutch FNPs experience, as suggested in the research literature and reports by monitoring bodies, considerable difficulties during their detention. They are barely aware of the prison rules and rights, they feel unsafe, socially excluded and unprepared for their return to society. It is clear that prison authorities are not sufficiently aware of these difficulties and because they are not addressed properly, FNPs are placed in a vulnerable position. The consular assistance which Dutch FNPs received from the Netherlands has however a positive effect. Those who receive assistance are less negative about their detention experience and this positive impact is visible in practically all aspects that were measured.

The support also addresses to a certain extent the special needs of Dutch FNPs. For example, the need to become aware of prison rules and legal procedures and the need to stay connected with the outside world. Personal visits were the most appreciated kind of assistance and these were found to have a very positive impact on the prisoner’s well being. In particular, the involvement of volunteers is worthwile. This innovative and cost-effective way to stay in contact with the prisoners is very much valued by them. The fact that their fellow country men and women, whom they did not know beforehand and who are unpaid, give them personal attention and support is powerful.

It is noteworthy that assistance by the Netherlands is mainly focussed on the well-being of the prisoner. It does not address the root causes of the difficulties that Dutch FNPs face. The fact that prisoners are detained in degrading conditions, are treated inhumanely and do not receive a fair trial is hardly addressed, even if the difficulties are directly connected to prison and/or judicial authorities not adhering to international, legally binding rules. This shows that there is no preventive element in the assistance and there is room for improvement.

Furthermore, the impact of consular assistance on the resettlement is not clear. Interviews with ex-prisoners revealed that it is very difficult to resettle in Dutch society after detention abroad. The two main reasons for this are the bureaucratic obstacles which they have to overcome, combined with a complete lack of attention and support from the local authorities. Municipalities are responsible for providing aftercare to ex-prisoners but they are often not aware of their citizens in foreign detention. When a citizen is abroad for longer than eight months, the municipality automatically deregisters him or her. Without registration it is not possible to apply for social benefits or to obtain, for example, a personal public service number. This number is required to be permitted to work, open a bank account, to make use of healthcare and to obtain an identity card.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that foreign authorities and organisations can make a difference in the detention experience of their nationals who are detained abroad. The Dutch model of providing consular assistance in cooperation with volunteers is effective and powerful. However, the Netherlands can do more to address concerns with foreign authorities when the basic rights of FNPs are not respected and when aftercare is provided to those who resettle into the Dutch society.

Further information

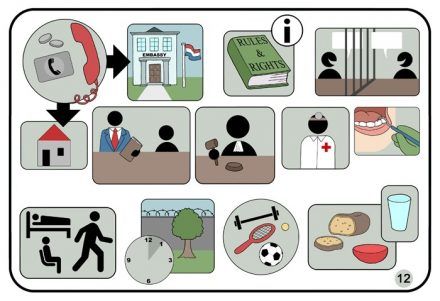

As part of the research, Prison Watch developed a universal picture dictionary for foreign detainees who don’t speak the language: ‘Picture it in prison’ can be downloaded for free on: www.prisonwatch.org/picture-it-in-prison.html. Currently in English, more languages to follow.